When you see an FDA safety alert about your medication, it’s easy to panic. You might think, ‘This drug is dangerous’ - and you’re not alone. But here’s the truth: most FDA safety announcements don’t mean you should stop taking your medicine. They mean the agency is watching closely. Understanding the difference between a potential signal and a confirmed risk can literally save your life - or prevent you from quitting a drug that’s keeping you alive.

What the FDA Actually Means by ‘Potential Signal’

The FDA doesn’t wake up one day and say, ‘This drug kills people.’ They see patterns. Every year, over 1.2 million adverse event reports pour into their system from doctors, pharmacists, and patients. These reports are raw data - not proof. A ‘potential signal’ is just a statistical hiccup: more people taking Drug X reported a rare kidney issue than expected. That’s it. It doesn’t mean Drug X caused it. It means they need to dig deeper. The FDA’s own documents say clearly: ‘The listing of a drug and a potential signal does not mean that FDA has determined that the drug has the risk.’ Yet most patients hear ‘FDA warns’ and assume the worst. In a 2022 survey, 75% of patients who read these alerts felt confused about whether to keep taking their meds. That’s not a failure of science - it’s a failure of communication.Why Some Alerts Cause More Fear Than They Should

Back in 2021, the FDA issued a safety notice about menstrual changes after COVID-19 vaccines. Thousands of women panicked. The alert didn’t say the vaccine caused irregular periods. It just said, ‘We’re seeing more reports than usual.’ Later, large studies confirmed: no causal link. The risk? About the same as skipping a period due to stress or caffeine. This isn’t rare. A 2022 BMJ analysis found that only 58% of FDA Drug Safety Communications clearly distinguish between ‘potential signal’ and ‘confirmed risk.’ That’s a problem. When a doctor gets an alert saying ‘Possible link between SSRI and birth defects,’ they don’t know if the risk is 1 in 10,000 or 1 in 100. Without numbers, they’re guessing. And patients? They’re terrified.How to Read an FDA Announcement Like a Pro

You don’t need a medical degree to make sense of these alerts. Here’s your five-step filter:- Check the language. Is it ‘potential signal,’ ‘possible association,’ or ‘confirmed risk’? If it says ‘possible,’ it’s not proven. If it says ‘risk increased,’ look for numbers.

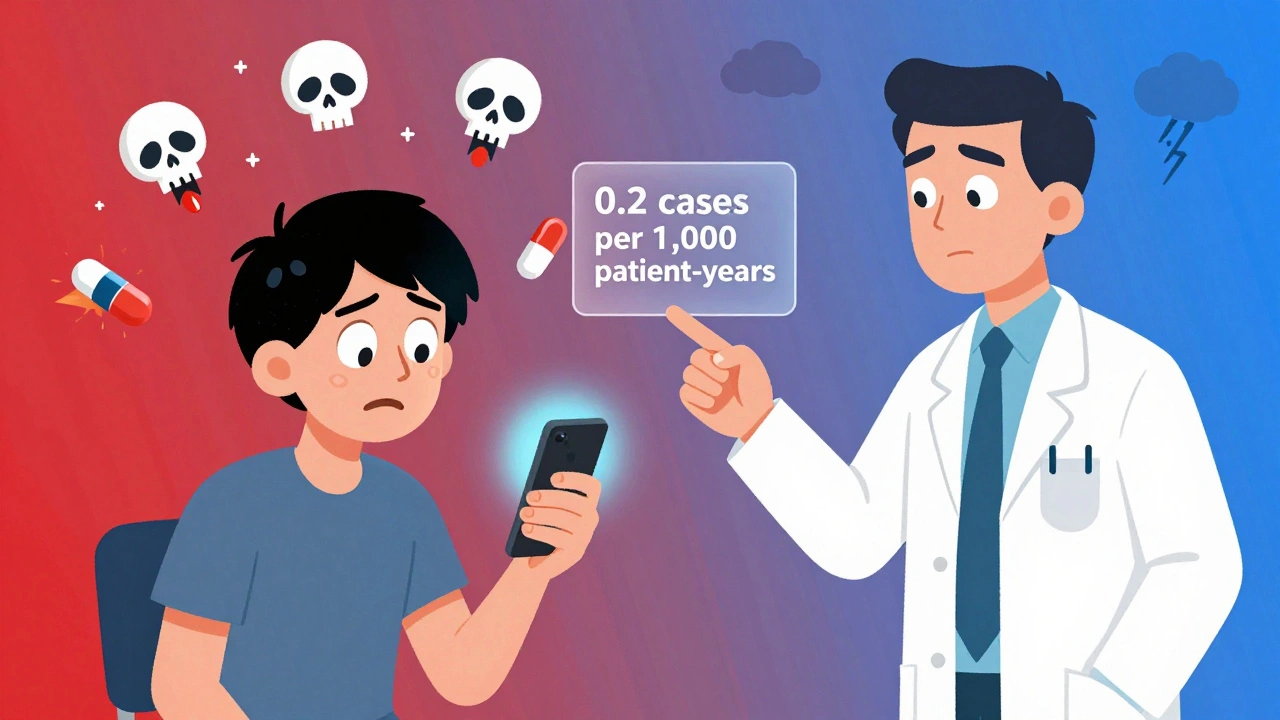

- Look for the baseline. What’s the risk without the drug? A 2022 alert on SGLT2 inhibitors for diabetes said Fournier’s gangrene occurred in 0.2 cases per 1,000 patient-years. That’s rare. But without knowing the baseline (0.06 in non-users), you can’t judge if it’s meaningful.

- Ask: Is this serious? The FDA defines serious as fatal, life-threatening, disabling, or requiring hospitalization. If the event is mild - nausea, headache, dizziness - it’s likely not a reason to stop.

- Is there a better option? If you’re on a drug for life-threatening cancer, a 1% risk of liver damage might be acceptable. If you’re on it for mild anxiety, that same risk might not be worth it. Benefit depends on context.

- Don’t stop cold turkey. The FDA almost never says ‘stop taking this.’ Even when a drug is pulled, it’s usually after years of evidence. If you’re worried, call your doctor - don’t Google and quit.

What the FDA Isn’t Telling You (But Should Be)

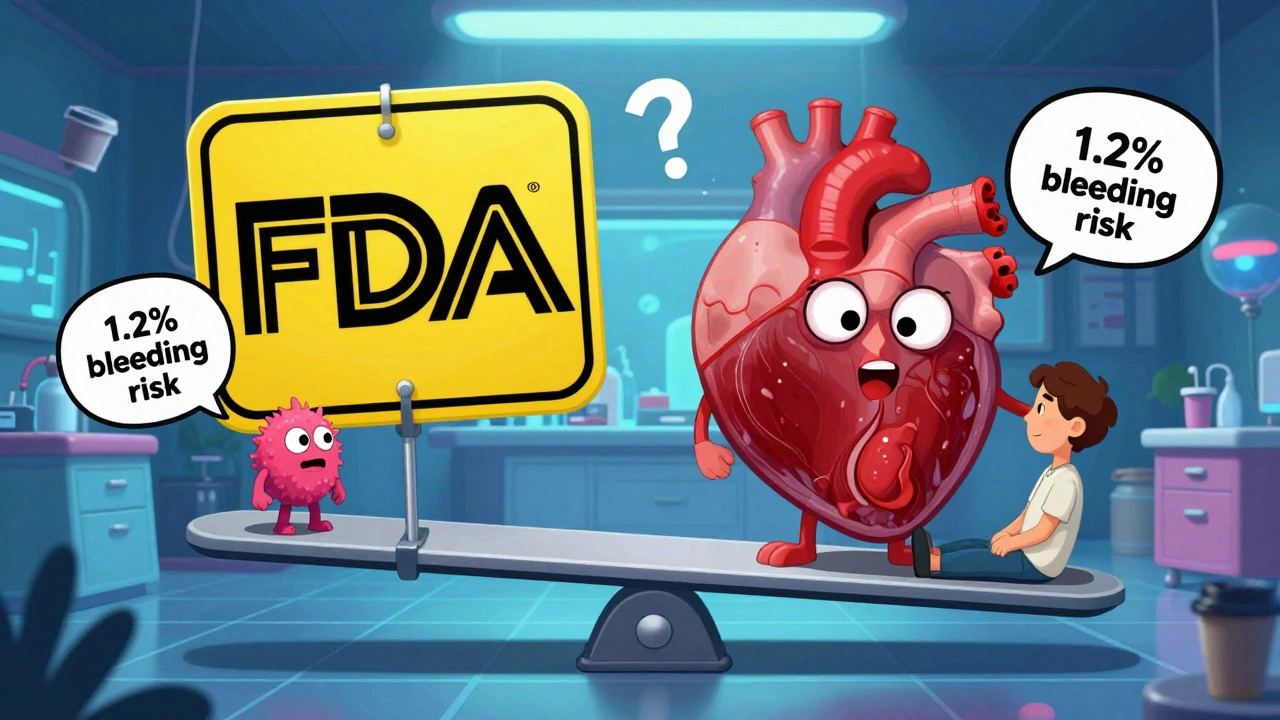

Experts agree: the FDA’s biggest flaw isn’t science - it’s storytelling. Dr. Thomas Moore from the Lown Institute pointed out in JAMA that FDA alerts rarely give quantitative risk estimates. That’s like saying ‘this car has a safety issue’ without telling you if it’s a loose hubcap or a broken brake line. The good news? That’s changing. In January 2024, the FDA released a new guidance document that requires all future risk-benefit assessments to include six clear elements: severity of the condition, available alternatives, magnitude of benefit, frequency and severity of risk, feasibility of managing the risk, and patient input. This isn’t just paperwork - it’s a shift toward transparency. By Q3 2025, the FDA plans to roll out standardized formats for risk numbers. Imagine an alert that says: ‘This drug reduces stroke risk by 30% but increases bleeding risk from 0.5% to 1.2% per year.’ That’s actionable. That’s useful. That’s what patients need.Real-World Impact: When Alerts Change Prescribing - For Better or Worse

In 2022, the American Medical Association surveyed 1,200 doctors. 42% said they changed their prescribing habits after an FDA alert - only to later find out the risk was minimal. One doctor stopped prescribing a common blood pressure drug after an alert about fainting. Later data showed the fainting rate was the same as in patients not on the drug. He’d overreacted. But sometimes, the alert saves lives. In 2020, the FDA flagged a rare but deadly liver injury linked to a diabetes drug. The signal was weak - only 12 cases over 5 years. But because the injury was fatal and irreversible, the FDA added a black box warning. Prescribing dropped. Deaths dropped too. The difference? Context. The first alert lacked numbers. The second had a clear, serious outcome. That’s what matters.

What You Should Do Right Now

If you’re on a medication and see a new FDA alert:- Don’t panic. Don’t stop.

- Find the original alert on fda.gov/drugsafety/ucm292512.htm. Read it yourself.

- Look for the word ‘confirmed’ - if it’s not there, it’s still being studied.

- Check if the alert includes numbers. If not, ask your doctor: ‘What’s the actual risk?’

- Ask: ‘Is this risk worse than the disease I’m treating?’

- Use the FDA’s Drug Safety Triaging Tool (updated monthly) - it cuts interpretation time by 35%.

Why This System Still Works - Even With Flaws

The FDA doesn’t get it perfect. But compared to other countries? It’s ahead. The European Medicines Agency waits years to publish signals. Japan waits for real-world data before acting. The FDA moves fast - sometimes too fast. But that speed catches dangers early. In 2022, the FDA issued 45 Drug Safety Communications. 65% led to labeling changes. 20% triggered new risk management plans. 15% led to new studies. That’s not chaos. That’s a system working. The goal isn’t to eliminate all risk. It’s to make sure the benefit outweighs the harm - and that patients and doctors know how to weigh it.Medicines are powerful. They heal. They kill. They change lives. The FDA’s job isn’t to scare you - it’s to give you the facts so you can decide. Your job? Don’t take their words at face value. Ask for the numbers. Ask for the context. And never make a life-changing decision based on fear alone.

Does the FDA issue safety alerts because drugs are unsafe?

No. The FDA issues safety alerts to monitor drugs after they’re on the market, not because they’re unsafe. All drugs have risks. The FDA’s job is to spot new or unexpected risks that weren’t clear during clinical trials. Most alerts are about potential signals - not confirmed dangers. Many turn out to be unrelated to the drug.

Should I stop taking my medication if I see an FDA safety alert?

Never stop a medication based on an alert alone. The FDA rarely advises stopping a drug without strong, confirmed evidence. Stopping suddenly can be dangerous - especially for blood pressure, antidepressants, or seizure meds. Contact your doctor first. They can help you weigh the real risk against the benefit.

What’s the difference between an adverse event and an adverse drug reaction?

An adverse event is any unwanted medical occurrence after taking a drug - whether or not the drug caused it. An adverse drug reaction is when there’s a reasonable chance the drug actually caused the problem. The FDA only acts on confirmed reactions, not just events. Most reports in their system are events, not reactions.

Why don’t FDA alerts include exact risk numbers?

Historically, the FDA didn’t always include quantitative risk data because it was hard to calculate from spontaneous reports. But that’s changing. Starting in 2024, new guidance requires risk estimates in all major communications. Alerts from 2022 onward, like the one on SGLT2 inhibitors and Fournier’s gangrene, already include numbers. If an alert lacks them, ask your doctor for the data.

How often does the FDA change drug labels after a safety alert?

About 65% of FDA Drug Safety Communications lead to labeling changes - like adding warnings, contraindications, or dosage limits. These changes happen after the agency confirms a risk and determines it’s significant enough to affect how the drug is used. Only about 20% result in new risk management programs, like requiring special training for prescribers.

Katie Harrison

December 9, 2025 AT 20:18Just read the FDA alert on my blood pressure med-no panic. I checked the numbers: bleeding risk went from 0.5% to 1.2% per year. My stroke risk dropped 30%. That’s not scary-it’s math.

Also, I called my pharmacist. They printed me a one-pager with the exact study links. Knowledge > fear.

Evelyn Pastrana

December 11, 2025 AT 00:38So the FDA finally stopped speaking in riddles? Took ‘em long enough.

Still, I’m just glad I didn’t quit my antidepressant after that one ‘possible link’ to weight gain. Turned out it was just people eating more pasta during lockdown. 🍝

ian septian

December 13, 2025 AT 00:15Don’t stop. Call your doctor. That’s it.

Arun Kumar Raut

December 14, 2025 AT 18:55As someone from India where meds are sold over the counter like candy, I’m glad the FDA even tries to explain this stuff.

Here, people stop insulin because they saw a TikTok about ‘toxic drugs.’ No numbers. No context. Just fear.

We need this kind of clarity everywhere.

Chris Marel

December 15, 2025 AT 01:58I’ve been on SSRIs for 8 years. When I saw the ‘possible birth defect’ alert, I almost quit. But I dug into the FDA’s own site. The risk was 1 in 10,000. My anxiety without the med? 1 in 2.

Thank you for writing this. I’m sharing it with my mom. She’s scared too.

Asset Finance Komrade

December 15, 2025 AT 07:09One must ask: is the FDA’s role to inform-or to manage the herd’s anxiety? The very structure of these alerts assumes the public is incapable of probabilistic reasoning. And so they weaponize ambiguity to maintain institutional authority.

It’s not about risk-it’s about control. The numbers, when provided, are treated as optional garnish, not the main course. A true epistemic humility would demand transparency as a moral imperative-not a 2024 guideline.

Still, I suppose we must be grateful for crumbs from the table of bureaucracy.

precious amzy

December 17, 2025 AT 03:31One cannot help but observe that the FDA’s shift toward quantitative risk communication is less a triumph of transparency and more a capitulation to the algorithmic mob that now dictates public health discourse.

Patients do not require ‘visual scales’-they require epistemic maturity. To reduce complex pharmacological trade-offs to a bar graph is to infantilize the very population one claims to serve.

And yet, one must concede: the alternative-vague, emotionally charged language-is far more insidious.

Carina M

December 17, 2025 AT 07:06It is unconscionable that any individual would consider discontinuing life-saving medication based on a social media post. This is not medical literacy-it is moral negligence.

The FDA’s warnings are not designed to frighten; they are designed to protect. Those who interpret them as threats are not victims-they are reckless.

Perhaps we should require a certification before one is allowed to read a drug label.

William Umstattd

December 17, 2025 AT 17:12Look. I’ve been on warfarin for 12 years. I’ve had three INR checks go off the charts. I’ve read every FDA alert ever written about it.

They don’t say ‘stop.’ They say ‘monitor.’

And yet, I still see people in online forums quitting because they saw ‘possible bleeding risk’ and thought it meant ‘you’re gonna die tomorrow.’

That’s not fear. That’s stupidity.

And the FDA? They’re not the problem. The people who don’t read the footnotes are.

Elliot Barrett

December 18, 2025 AT 20:33Why do we even need this guide? If you can’t read a medical alert without panicking, maybe you shouldn’t be on meds.

It’s not rocket science. If it says ‘possible,’ it’s not real. If it says ‘risk,’ check the number. If there’s no number, ask your doctor.

That’s it. That’s the whole thing.

Stop making it a drama.

Steve Sullivan

December 20, 2025 AT 11:30Okay, but let’s be real-this whole system is still built on a lie.

The FDA says ‘potential signal’ but the media screams ‘DRUG KILLS.’

Doctors get scared and stop prescribing. Patients get scared and quit. The science? It’s still in the lab.

And yet, we treat these alerts like gospel because we don’t trust our own brains to do the math.

It’s not the FDA’s fault. It’s ours. We’ve outsourced our critical thinking to headlines.

And now we’re shocked when we panic over a 0.2% risk?

Wake up. The system’s not broken. We are.