Aminoglycoside Nephrotoxicity Risk Calculator

Patient Risk Assessment

This calculator estimates your risk of developing kidney damage while taking aminoglycoside antibiotics based on key risk factors.

When you’re fighting a serious bacterial infection, especially one caused by tough Gram-negative bugs like E. coli or Pseudomonas, doctors often turn to aminoglycoside antibiotics. Drugs like gentamicin, tobramycin, and amikacin are powerful - they kill bacteria fast. But there’s a dark side: these drugs can damage your kidneys. About 1 in 5 people who take them for more than a few days will develop some level of kidney injury. That’s not rare. It’s expected. And it’s preventable - if you know what to watch for.

How Aminoglycosides Hurt the Kidneys

Aminoglycosides don’t attack your kidneys on purpose. They just get stuck there. After being filtered by the glomeruli, about 5% of the drug sticks to the cells lining the proximal tubules - the part of the kidney that reabsorbs nutrients and water. Once inside, they pile up in lysosomes, the cell’s recycling centers. That’s where the trouble starts.

These drugs interfere with phospholipid breakdown. They bind to negatively charged membranes, jamming up enzymes that keep cells clean. Over time, lysosomes swell into giant, empty-looking sacs called myeloid bodies. You can see them under an electron microscope - they’re like little toxic time bombs. Mitochondria get damaged. The endoplasmic reticulum gets stressed. Cells start dying. And when enough of them go, kidney function drops.

What’s surprising is that it’s not just the tubules. For years, doctors thought the damage was purely tubular. But research since 2011 shows that aminoglycosides also cause renal vasoconstriction. Blood flow to the kidneys drops. The tiny vessels around the glomeruli tighten. That’s why creatinine rises - not just because tubules are clogged, but because less blood is getting filtered.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone who gets aminoglycosides gets kidney damage. But some people are far more vulnerable.

- Older adults - over 65, the risk jumps because kidneys naturally lose function with age.

- People with existing kidney problems - if your eGFR is below 60 mL/min/1.73m², you’re 3.2 times more likely to suffer injury.

- Those on other nephrotoxic drugs - especially vancomycin. Taking both increases your risk by 2.7 times.

- Dehydrated patients - low blood volume means less drug clearance and more concentration in the kidneys.

- People on long courses - risk climbs after day 5. Beyond 7 days, it’s almost guaranteed if no precautions are taken.

One study at Mayo Clinic followed 1,247 patients. Nearly 19% developed acute kidney injury. Most recovered - but not all. About 1 in 5 had lasting damage.

What Does Kidney Damage Look Like?

Aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity doesn’t look like other kinds of kidney failure. It’s usually nonoliguric - meaning you’re still peeing. A lot. More than 400 mL a day, even when your kidneys are failing. That’s why it’s easy to miss.

The first sign? A slow rise in serum creatinine. A jump of 0.5 mg/dL or 50% above your baseline is a red flag. It usually shows up after 5-7 days of treatment.

Before creatinine rises, your urine changes. You’ll start spilling electrolytes - sodium, potassium, magnesium, calcium. Your urine gets dilute, not concentrated. Proteins like beta-2-microglobulin and enzymes like N-acetylglucosaminidase show up in urine tests. These are early warning signs, detectable in labs before your creatinine climbs.

By the time creatinine is high, the damage is already underway. That’s why monitoring isn’t enough - you need to look for the hidden signals.

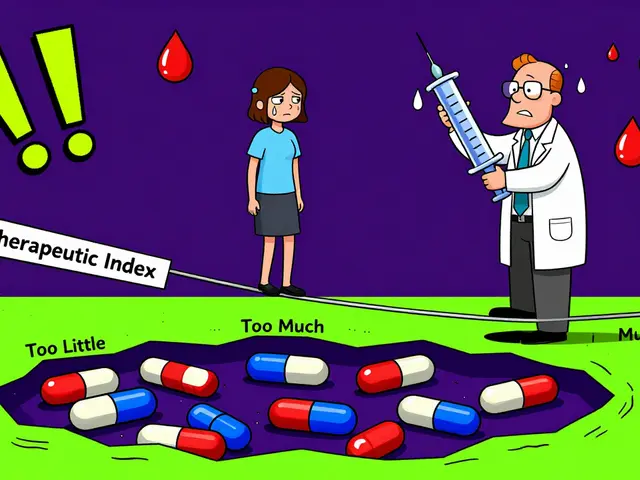

Dosing Matters More Than You Think

It’s not just how much you give - it’s how often.

For decades, aminoglycosides were given every 8 hours. But research from 2003 showed that giving the same total daily dose in three smaller doses causes faster, worse kidney damage than giving it all at once. Why? The kidneys get hit repeatedly. There’s no time to recover.

Now, once-daily dosing is standard. It’s more effective against bacteria and much gentler on the kidneys. The drug floods the system once, gets taken up by bacteria, then clears out before it can pile up in tubules.

Even the time of day matters. One study found that giving the dose at 1:30 p.m. led to the lowest nephrotoxicity rates. Why? Circadian rhythms affect kidney blood flow and tubule activity. Giving the drug when the kidney is most active may reduce accumulation.

Comparing Aminoglycosides: Gentamicin vs. Amikacin

Not all aminoglycosides are equal. Gentamicin is the most studied - and the most nephrotoxic. At the same dose, it causes more kidney damage than amikacin. Tobramycin is in between.

Why? It’s about molecular structure. Gentamicin binds more tightly to kidney cell membranes. Amikacin has an extra side chain that makes it less sticky. That small change reduces uptake by tubule cells.

Still, all aminoglycosides carry risk. Switching from gentamicin to amikacin doesn’t eliminate danger - it just lowers it. You still need monitoring.

Can You Prevent It?

Yes - but not with magic pills. There’s no approved drug to protect your kidneys from aminoglycosides… yet.

Here’s what works now:

- Once-daily dosing - stick to it. Don’t go back to 3x/day unless there’s a clear reason.

- Monitor creatinine every 48-72 hours - don’t wait for symptoms.

- Keep trough levels low - for gentamicin, keep it under 1 μg/mL. That’s the target.

- Avoid other kidney toxins - hold off on vancomycin, NSAIDs, contrast dye if possible.

- Hydrate - keep the patient well-fluided. IV fluids aren’t optional.

- Limit duration - if you can treat the infection in 5 days, don’t give 10.

There’s promising research on polyaspartic acid. In animals, it blocks aminoglycosides from sticking to kidney cells. It stops lysosomal damage, prevents myeloid body formation, and protects kidney function. But it’s not approved for humans yet. Phase II trials are ongoing, but don’t expect it on the shelf next year.

Recovery: Is the Damage Permanent?

Most people recover. In the Mayo Clinic study, 82% had partial or full kidney function return within 30 days of stopping the drug. Recovery usually starts 3-5 days after the last dose. Creatinine drops slowly. It can take weeks.

But not everyone. About 1 in 5 ends up with permanent kidney damage - especially if they were older, had pre-existing disease, or were on the drug too long. The kidneys can regenerate, but only if the damage isn’t too deep. Once tubule cells die and scar tissue forms, function doesn’t come back.

Some studies in rats show something fascinating: after weeks of high-dose gentamicin, the kidneys adapt. New, less-differentiated cells form. These cells don’t take up the drug as easily. The kidney becomes resistant. That might explain why some patients on long-term therapy don’t crash - their kidneys learned to avoid the poison.

Why We Still Use These Drugs

If they’re so dangerous, why do we still use them?

Because sometimes, there’s no alternative. For multidrug-resistant infections - like those caused by carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella or Pseudomonas - aminoglycosides are one of the few options left. The WHO estimates 12.5 million courses are used globally every year. These drugs save lives when nothing else works.

They’re cheap. They’re fast. And for critically ill patients, the risk of death from infection outweighs the risk of kidney damage.

But that doesn’t mean we should be careless. Every time you prescribe an aminoglycoside, you’re making a trade-off. Know the risks. Monitor closely. Minimize exposure. And never assume the patient is safe just because their creatinine hasn’t spiked yet.

The Future: Better Drugs, Better Protection

Researchers are working on three fronts:

- New aminoglycoside derivatives - chemists are tweaking the molecules to keep antibacterial power but reduce kidney binding.

- Targeted protectants - polyaspartic acid analogs, antioxidants, apoptosis blockers - are being tested in clinical trials. One compound (NCT04567821) is in Phase II across six U.S. hospitals.

- Personalized dosing - using genetic markers or real-time biomarkers to predict who’s most at risk before giving the drug.

For now, the best protection is still vigilance. Know your patient. Know the drug. Know the signs. And don’t wait for the creatinine to rise before you act.

Ryan W

January 26, 2026 AT 06:56Aminoglycosides are a necessary evil. We’re talking about life-or-death infections here - if you’re septic from a CRE strain, you don’t get to pick your poison. But yeah, the nephrotoxicity is real. I’ve seen residents miss the nonoliguric pattern and think the patient’s fine because they’re peeing. Nope. That’s the trap. Creatinine doesn’t rise until the tubules are already fried. Monitor urine sodium, beta-2-microglobulin, NAG - if you’re not, you’re doing it wrong.

Rakesh Kakkad

January 26, 2026 AT 20:02It is imperative to note that the pathophysiological mechanism of aminoglycoside-induced nephrotoxicity involves lysosomal phospholipidosis, which is mediated by the binding of cationic drug molecules to anionic phospholipids in the proximal tubular epithelial cells. This phenomenon leads to the formation of myeloid bodies, which are pathognomonic under electron microscopy. The renal vasoconstriction component, often overlooked, is mediated by endothelin-1 upregulation and nitric oxide suppression. Clinical vigilance must extend beyond serum creatinine to include fractional excretion of sodium and urinary biomarkers.

Nicholas Miter

January 27, 2026 AT 21:17Man, I’ve seen so many patients on gentamicin and nobody checks their troughs. I get it - busy floor, tired docs. But 1 μg/mL is the sweet spot. Go above that and you’re just gambling with someone’s kidneys. And honestly? Once-daily dosing isn’t just safer - it’s easier. Less paperwork, less confusion. Plus, the data’s solid. If your hospital still does 8-hour schedules for routine cases, they’re stuck in the 90s.

Also, hydration isn’t optional. I had a guy on vanco + gent who was dehydrated from vomiting. His creatinine jumped from 1.1 to 4.8 in 72 hours. He needed dialysis for a week. All because no one gave him fluids. Don’t be that team.

Suresh Kumar Govindan

January 29, 2026 AT 01:36Who funds this research? Pharma? The WHO? The fact that polyaspartic acid is in Phase II and not approved speaks volumes. There is a deliberate suppression of kidney-protective agents to maintain demand for dialysis, renal transplants, and long-term nephrology care. This is not science - it is economics disguised as medicine.

George Rahn

January 30, 2026 AT 10:23Let’s be real - we’re playing Russian roulette with antibiotics and calling it ‘evidence-based.’ We’re told to use aminoglycosides because they’re cheap and fast, but we ignore the long-term cost: chronic kidney disease, dialysis, lost productivity, depression. This isn’t treatment - it’s triage with a white coat. And the worst part? We know better. We just don’t have the political will to change. The system doesn’t reward prevention. It rewards crisis management.

And don’t get me started on how we treat the elderly. ‘Oh, they’re 78, their kidneys are already gone.’ No. Their kidneys are trying to survive your dosing schedule.

Karen Droege

January 31, 2026 AT 00:33Y’all need to stop acting like nephrotoxicity is some mysterious force of nature. It’s not. It’s predictable. It’s preventable. And it’s happening because we’re lazy or overworked or just don’t care enough. I’ve been in the ICU for 12 years. I’ve watched 3 patients go from ‘just a quick 5-day course’ to needing lifelong dialysis because someone didn’t check a trough or hold vancomycin. We are the last line of defense. Stop waiting for labs to scream. Listen to the patient. Listen to the numbers. Listen to your gut.

And yes - amikacin is better than gentamicin. Not perfect. Better. Use it when you can. And if your pharmacy says ‘no stock’ - push back. Your patient’s kidneys are worth the fight.

Shweta Deshpande

February 1, 2026 AT 22:26I just wanted to say thank you for writing this - I’m a nurse in a rural hospital and we don’t always have the resources to monitor everything, but this made me feel less alone. We’ve had a few scary cases where creatinine spiked after day 6 and we didn’t know why. Now I’m printing this out and sharing it with the whole team. I even showed my mom (she’s 72 and on gentamicin for a UTI) and she said, ‘Honey, you’re smarter than the doctors.’ That’s not a compliment - that’s a warning. We need to do better.

Also, hydration is everything. I make sure everyone gets at least 1L of IV fluid before their aminoglycoside. Not because it’s in the protocol - because I’ve seen what happens when we don’t.

Sally Dalton

February 2, 2026 AT 10:23so like… i just read this whole thing and i’m crying?? not because i’m sad, but because i finally understand why my grandma’s kidneys never bounced back after her pneumonia. they gave her gentamicin for 10 days and she was ‘fine’ until she wasn’t. no one told us it could be permanent. we thought it was just ‘old age.’ this is so important. thank you.

Shawn Raja

February 2, 2026 AT 11:40So let me get this straight - we have a drug that kills superbugs, but we’re scared of its side effects… so we give it once a day, hydrate the patient, and monitor like hawks… but still call it ‘necessary evil’? Nah. That’s not evil. That’s just bad management. The real evil is when we use it like a hammer because we don’t have a scalpel. We need better antibiotics. Not just better dosing. We need innovation. Not just vigilance.

Also, the 1:30 p.m. dosing thing? That’s wild. Circadian rhythms matter. Your liver, your kidneys, your gut - they all have a schedule. We treat the body like a machine that runs 24/7. It’s not. It’s a symphony. And we’re conducting it with a baseball bat.

Dan Nichols

February 3, 2026 AT 05:32Everyone’s acting like this is new info but it’s been in UpToDate since 2015. If you didn’t know this, you’re not a bad person - you’re just untrained. Stop acting like you’re saving lives by reading a Reddit post. Real medicine is in the textbooks, not in the comments section. Also, amikacin isn’t magically safe - it’s just slightly less toxic. Still nephrotoxic. Still needs monitoring. Still kills kidneys if you’re dumb.

Renia Pyles

February 3, 2026 AT 23:45Of course they’re gonna say it’s preventable. That’s what they always say. Then they say ‘we didn’t know’ after the patient dies. And then they write another article like this. And then someone else dies. And then another. And then another. This isn’t medicine. It’s a ritual. A sacrifice. We give the drug. We watch the creatinine rise. We shrug. We say ‘it’s the disease, not the drug.’ Bullshit. It’s the drug. Always has been. Always will be.

Josh josh

February 5, 2026 AT 18:06just read this on my lunch break and i’m so glad i did. i work in a nursing home and we had a guy on gentamicin for 12 days. no one checked his labs after day 5. he went from walking to bedbound. we thought it was dementia. turns out it was kidney failure. this post saved me from making the same mistake. thanks for writing this.