When your baby’s skin is dry, red, and itchy, it’s easy to think it’s just a rash. But for many families, that rash is the first sign of something bigger - a chain reaction called the atopic march. It’s not a guarantee that your child will develop asthma or food allergies, but it does mean their skin is sending a signal: something in their immune system is out of balance. And the good news? What you do now - especially with their skin - can change the path ahead.

What Is the Atopic March, Really?

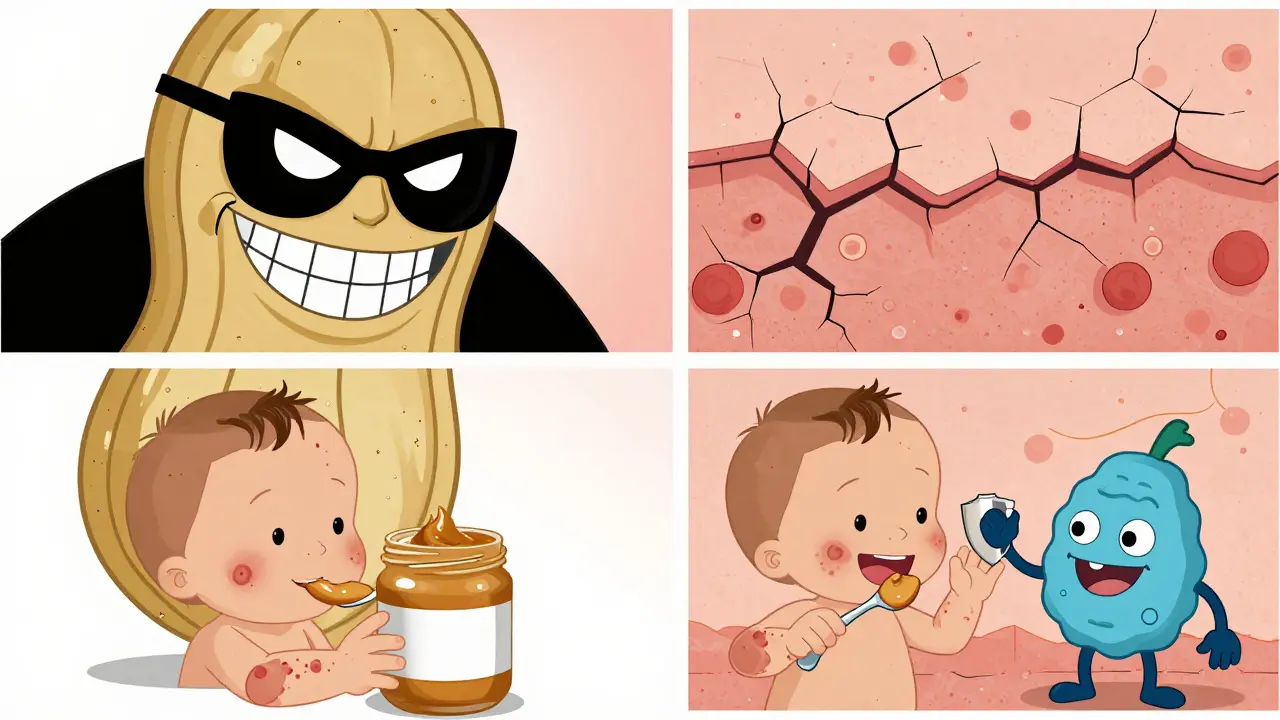

The atopic march used to be taught like a straight line: eczema first, then food allergies, then asthma, then hay fever. But that’s not how it works for most kids. Recent studies show only about 3.1% of children with eczema follow that exact order. Instead, we now call it atopic multimorbidity - meaning these conditions often show up together, overlap, or appear in different orders. Still, eczema remains the most common starting point. Around 17-24% of children worldwide develop it, often before they’re six months old.Why does it start with the skin? Because that’s where the breakdown begins. In babies with eczema, the outer layer of skin doesn’t work like it should. Think of it like a brick wall with missing mortar. Tiny cracks let in dust, pollen, peanut particles, even milk proteins - things that should stay outside. When these allergens slip through, the immune system panics. It starts making IgE antibodies, which set off inflammation. That’s how a rash turns into a food allergy, or how a dry patch leads to wheezing months later.

The Skin Barrier Is the First Line of Defense

Your baby’s skin isn’t just a covering - it’s a living shield. One key player in that shield is a protein called filaggrin. It holds skin cells together and keeps moisture in. About 1 in 5 people with eczema have a genetic mutation that reduces filaggrin. That doesn’t mean they’ll definitely get allergies - but without it, their skin is more vulnerable. Other genes like SPINK5 and those affecting corneodesmosin also weaken the barrier. And it’s not just genetics. Harsh soaps, hot baths, low humidity, and even certain fabrics can damage the skin’s surface over time.Here’s what that looks like in real life: a newborn with dry, flaky cheeks. Parents might rub in lotion, but if they wait until the skin cracks, it’s already too late. The real window for prevention is before those cracks form. Studies show babies with dry skin at birth are more likely to develop eczema and food allergies by age one. That’s not coincidence - it’s cause and effect.

How Skin Exposure Leads to Allergies

The LEAP study changed everything. Researchers gave high-risk infants - those with severe eczema - a small amount of peanut protein to eat, starting at 4-11 months. By age five, those kids were 86% less likely to develop a peanut allergy than those who avoided it. Why? Because eating peanut taught the immune system to tolerate it. But if the same peanut protein touched broken skin first - say, through a cream or a wipe - the body saw it as an invader. That’s the dual-allergen exposure hypothesis: skin = sensitization, mouth = tolerance.It’s the same with eggs and cow’s milk. If your baby has eczema and you avoid these foods, you’re not protecting them - you might be setting them up for trouble. The skin is the wrong entry point. The gut is where the immune system learns what’s safe. That’s why experts now recommend introducing common allergens early and often, even if your child has eczema - as long as it’s done safely, under guidance.

How Severe Eczema Changes the Game

Not all eczema is the same. Mild cases might clear up by age two. But severe eczema? That’s a different story. Kids with intense, persistent rashes are three to four times more likely to develop asthma, allergic rhinitis, or multiple allergies. The BAMSE study found that children with severe eczema had over a 60% higher chance of developing asthma by age seven compared to those with mild cases. And among kids who already have asthma, 74-81% also have allergic rhinitis - usually starting around age three.Here’s the key: it’s not the eczema itself that causes asthma. It’s the level of skin damage and immune disruption. The more inflamed and cracked the skin, the more signals it sends to the immune system to go on high alert. Genes like TSLP and IL-33 are involved in this process - they’re like alarm buttons that get stuck in the “on” position when the skin barrier fails. That’s why treating eczema aggressively isn’t just about comfort - it’s about preventing bigger problems down the road.

What You Can Do: Skin Barrier Care That Works

The PreventADALL trial is one of the most important studies in this field. Researchers gave daily emollients (moisturizers) to newborns at high risk for eczema - starting right after birth and continuing for at least six months. The result? A 20-30% drop in eczema cases. That’s huge. It means protecting the skin barrier before it breaks can stop the march before it starts.Here’s what works in real life:

- Use fragrance-free, thick moisturizers - think ointments or creams, not lotions. Look for ingredients like ceramides, cholesterol, and fatty acids. These rebuild the skin’s natural barrier.

- Apply moisturizer at least twice a day, even on days when the skin looks fine. Don’t wait for dryness.

- Bath time should be short (5-10 minutes), lukewarm, and gentle. Skip bubble baths and scented soaps. Pat skin dry - don’t rub.

- Use cotton clothing. Avoid wool and synthetic fabrics that irritate.

- Keep humidity in your home above 40%. Dry winter air in Manchester? Use a humidifier in the bedroom.

And yes - start early. The first 100 days of life are critical. That’s when the immune system is learning what’s friend or foe. If the skin barrier is strong during this time, it helps the body stay calm around allergens.

The Gut-Skin Connection

It’s not just the skin. The gut plays a role too. Babies who develop multiple allergies often have different gut bacteria - ones that don’t make enough butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid that calms inflammation. Studies show these babies have less of the microbes that ferment fiber into protective compounds. That’s why some researchers are testing probiotics and prebiotics to see if they can help. It’s not a magic fix, but it’s another piece of the puzzle. A healthy gut might help the immune system stay balanced - especially when the skin is under stress.When to Worry - And When Not To

Most kids with eczema won’t go on to develop asthma or food allergies. Only about 25% do. But if your child has severe eczema, early-onset rashes, or a family history of asthma or allergies, you’re in a higher-risk group. That doesn’t mean panic - it means awareness. Talk to your doctor about early allergen introduction. Don’t avoid peanut butter or eggs because you’re scared. Ask how to introduce them safely.Also, don’t confuse sensitization with allergy. A blood test might show your child is “sensitized” to milk - meaning their body made antibodies. But if they eat milk without a reaction, they’re not allergic. Sensitization alone doesn’t need treatment. Only clinical symptoms - hives, vomiting, wheezing - do.

The Future Is Precision, Not Prediction

We’re moving away from saying “all kids with eczema will get asthma.” That’s outdated. Now, doctors are building tools to predict who’s at real risk - using genetics, skin severity, microbiome data, and environmental factors. This isn’t science fiction. In the UK, research teams are already testing algorithms to spot high-risk babies before age one. The goal? To give targeted care - not blanket advice.For now, the best thing you can do is protect the skin. Treat eczema early and well. Use moisturizers daily. Introduce allergens safely. Watch for signs of breathing trouble or reactions after eating. And remember - this isn’t about perfection. It’s about giving your child’s body the best chance to grow strong, not overreact.

Does eczema always lead to allergies?

No. Only about 25% of children with eczema go on to develop asthma or food allergies. Most outgrow their eczema without other allergic conditions. The risk is higher with severe eczema, family history, or early-onset rashes - but it’s not guaranteed.

Can moisturizing prevent food allergies?

It can help reduce the risk. The PreventADALL trial showed daily emollient use from birth lowered eczema incidence by 20-30%. Since eczema is the first step in the atopic march, protecting the skin may lower the chance of allergens entering through cracks - which reduces sensitization. But moisturizing alone isn’t enough - early oral introduction of allergens like peanut is also key.

When should I introduce peanut to my baby with eczema?

For babies with severe eczema or egg allergy, introduce peanut between 4 and 11 months - but do it safely. Talk to your doctor first. They may recommend an allergy test or supervised first feeding. For mild to moderate eczema, introduce peanut around 6 months along with other solids. Never give whole peanuts - use peanut butter thinned with water or a peanut powder mixed into food.

What’s the best moisturizer for eczema-prone skin?

Look for ointments or thick creams with ceramides, cholesterol, and fatty acids. Brands like CeraVe, Eucerin, and A-Derma are often recommended. Avoid products with fragrance, alcohol, or essential oils. Ointments (like petroleum jelly) work best for very dry skin - they lock in moisture better than lotions.

Is the atopic march still a useful concept?

Yes - but not as a fixed path. The old idea of a strict sequence is outdated. Today, we see it as a pattern of overlapping conditions driven by skin barrier failure and immune overactivity. It’s still useful for identifying high-risk children and guiding early interventions - but only if we focus on individual risk, not assumptions.

Rachel Liew

January 31, 2026 AT 17:21i just found out my 6-month-old has eczema and honestly i thought it was just dry skin from the heater. now i feel like i should’ve been moisturizing since day one 😅

Angel Fitzpatrick

February 1, 2026 AT 13:29They don’t want you to know this but the pharmaceutical industry *loves* eczema. Why? Because it’s a cash cow. Moisturizers? Cheap. But if you convince moms to buy $80 ‘ceramide creams’ and then push immunosuppressants later? That’s the real atopic march - the one they profit from. The skin barrier? A myth. It’s all about glyphosate in baby food and EMF exposure. Wake up.

Lilliana Lowe

February 3, 2026 AT 00:30It’s rather disappointing that the article conflates correlation with causation in the context of the atopic multimorbidity paradigm. The LEAP study, while groundbreaking, does not establish that transcutaneous allergen exposure is the *sole* pathway to sensitization - nor does it account for epigenetic modulation via maternal microbiome transfer. Furthermore, the assertion that emollients reduce eczema incidence by 20–30% is derived from a single cohort study with significant selection bias. The PreventADALL trial’s primary endpoint was not allergy prevention but eczema severity reduction - a critical distinction often overlooked in lay summaries.

Naresh L

February 3, 2026 AT 04:58Isn’t it strange how we treat the skin like a wall, when it’s more like a breathing membrane? We try to seal it, protect it, control it - but maybe the body isn’t broken. Maybe it’s trying to tell us something. The immune system doesn’t panic without reason. What if the real problem isn’t the barrier… but the world we’ve built around it? Clean too much. Eat too little fiber. Fear too many foods. Maybe healing isn’t about fixing the skin - but letting it be part of a living system again.

franklin hillary

February 4, 2026 AT 20:29Y’all need to hear this - your baby’s skin is their first teacher. If you don’t moisturize like it’s oxygen, you’re basically handing your kid a one-way ticket to asthma. I’ve seen it. My nephew had cradle cap at 3 weeks. We started CeraVe twice a day. By 6 months? No eczema. By 18 months? Ate peanut butter straight from the jar. No allergies. No drama. Just strong skin and a happy kid. Do the work. It’s not hard. It’s just consistent.

Aditya Gupta

February 5, 2026 AT 16:04moisturize early. introduce peanut early. dont panic. its not magic but its science. my niece did this and now she eats everything. no wheezing. no rashes. just a kid who loves peanut butter sandwiches. simple stuff works.

Nancy Nino

February 6, 2026 AT 23:03How quaint. A 20% reduction in eczema? That’s not prevention - that’s a placebo with a price tag. You’re telling parents to slather on petroleum jelly while the world floods their environment with endocrine disruptors? The real solution is systemic change - not another $30 cream. 😌

June Richards

February 8, 2026 AT 18:34Ugh I’m so tired of this ‘skin barrier’ nonsense. My kid had eczema and we did ALL the things - ceramides, humidifiers, cotton, no soap - and still got a peanut allergy. So congrats, science, you gave me guilt and a $200 moisturizer. 🙄

Jaden Green

February 8, 2026 AT 20:10Let’s be real - this whole atopic march narrative is just a convenient framework for pediatricians to sell more products and more tests. They’ll tell you to moisturize, then they’ll tell you to test for IgE, then they’ll tell you to avoid allergens - until you’re broke, anxious, and still have a screaming baby with cracked skin. Meanwhile, the real triggers - processed foods, antibiotics in infancy, lack of outdoor exposure - are never mentioned. This isn’t medicine. It’s fear-based marketing dressed up as science.

Lu Gao

February 10, 2026 AT 07:32Wait - so the ‘dual-allergen hypothesis’ means we should feed our babies peanut butter… but avoid putting it on their skin? 😂 That’s literally the opposite of what my aunt did in 1998. She rubbed peanut butter on my eczema and I turned into a human balloon. So… maybe we should just stop touching everything with our hands? 🤔

Nidhi Rajpara

February 11, 2026 AT 21:46I am a pediatric nurse and I must say, the data is clear: early emollient use reduces barrier disruption. However, many parents misunderstand the application technique. It is not sufficient to apply once daily. The correct protocol requires 2–3 applications per day, ideally after bathing, with gentle patting, not rubbing. Furthermore, the choice of product matters - mineral oil-based emollients may be less effective than those containing ceramides. Please consult your pediatrician before initiating any regimen.

Chris & Kara Cutler

February 12, 2026 AT 18:18WE DID THIS. OUR KID IS 1. NO ECZEMA. NO ALLERGIES. JUST A HAPPY BABY WHO EATS PEANUT BUTTER OUTTA HER FIST. 🙌

Jamie Allan Brown

February 12, 2026 AT 21:48I grew up in rural Scotland with no moisturizer, dirt under my nails, and goats licking my face. I had eczema as a kid. So did my brother. Neither of us developed allergies. Maybe the real lesson isn’t just about skin - it’s about connection. To earth. To animals. To messy, unsterile life. We’ve sanitized ourselves into a crisis. The skin doesn’t need to be perfect. It needs to be alive.

Lisa Rodriguez

February 13, 2026 AT 01:42My daughter had severe eczema at 3 months. We started moisturizing religiously and introduced peanut at 5 months with her pediatrician. At 18 months she’s eating eggs, dairy, nuts - no reactions. No asthma. No anxiety. I get why people are scared. But you don’t have to be. Just start small. Talk to your doctor. And don’t wait for perfect. Just start.