Most people think patent protection for drugs ends when the patent expires. But that’s not always true. For many medications, even after the patent runs out, generic versions still can’t hit the market-for another six months. That’s not because of a longer patent. It’s because of something called pediatric exclusivity.

What pediatric exclusivity actually does

Pediatric exclusivity doesn’t extend the patent. It doesn’t change the date the patent expires. Instead, it blocks the FDA from approving generic versions of a drug for six extra months, even if the patent is already gone. This is a regulatory delay, not a legal one. The patent might be dead, but the FDA still can’t give final approval to any competitor product until that six-month clock runs out. This rule comes from Section 505A of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. It was created to fix a real problem: drugs were being given to kids all the time, but almost no studies had been done to figure out the right doses, safety, or side effects for children. So the FDA started offering a reward: six months of extra market protection if a drugmaker studies their medicine in kids. The key here is that the company doesn’t have to change the label or get a new approval. They just need to do the right studies, submit them, and prove they followed the FDA’s written request. Once the FDA accepts the reports, the six-month clock starts ticking-no matter what else is going on with patents or other exclusivities.How it connects to existing protections

Pediatric exclusivity doesn’t work alone. It attaches to whatever other exclusivity the drug already has. That could be:- Five years of new chemical entity (NCE) exclusivity

- Three years of exclusivity for new clinical studies

- Orphan drug exclusivity (seven years)

It applies to every version of the drug

Here’s where it gets powerful. If a company makes a drug in three forms-oral tablets, liquid syrup, and topical cream-and they all contain the same active ingredient, pediatric exclusivity covers all of them. It doesn’t matter if the pediatric studies were only done on the tablet form. The six-month delay applies to every dosage form and every approved use, as long as the active moiety is the same. That means a drugmaker can get a six-month market advantage across multiple products with just one set of pediatric studies. It’s a huge incentive. For a blockbuster drug like a popular ADHD medication or a common antibiotic, six months of exclusive sales can mean hundreds of millions in extra revenue.

What happens when the patent expires?

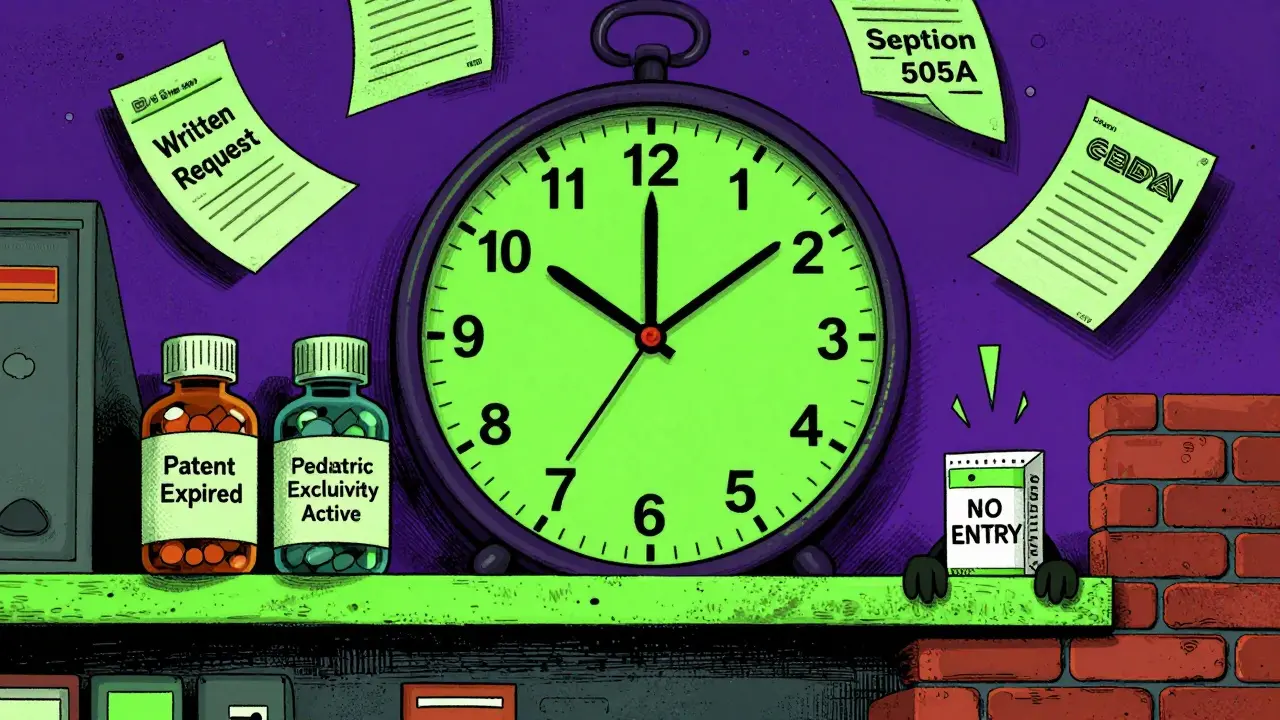

This is where most people get confused. If a drug’s patent expires but pediatric exclusivity is still active, the FDA still can’t approve generics. The patent is gone, but the exclusivity remains. Generic companies can still file applications, but the FDA will hold them until the six months are up. Even if a generic applicant files a Paragraph II certification (meaning they say the patent has expired), the FDA still can’t approve the drug during pediatric exclusivity. The exclusivity becomes the only barrier. Courts have upheld this. The FDA has the legal right to treat expired-patent applications as if they’re still blocked-because the exclusivity is a separate regulatory hurdle. There’s only one way around it: the brand company must give a waiver, or a court must rule that the patent is invalid or not infringed. But if the patent is already expired, a court ruling doesn’t help. Only a waiver from the original drugmaker can unlock approval early.Who can’t use it?

Pediatric exclusivity only applies to small-molecule drugs. It doesn’t work for biologics. That’s because biologics are regulated under a different law-the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA). Under that law, patents don’t block FDA approval of biosimilars the same way they do for generics. So even if a biologic company does pediatric studies, they don’t get the six-month exclusivity bonus. Also, if a drug has no patent and no other exclusivity left, pediatric exclusivity usually won’t apply. But there’s an exception: if the company submits a new application to expand the drug’s use to children, and that application requires new clinical data, then the FDA can grant pediatric exclusivity even if nothing else is protecting the drug. That’s rare, but it happens.

Why it matters for generic companies

For generic manufacturers, pediatric exclusivity is a major roadblock. They might think they’re clear to launch after a patent expires, only to find out they’re blocked by a six-month exclusivity they didn’t even know existed. That’s why smart generic companies track the Orange Book closely and monitor FDA decisions on pediatric exclusivity grants. If they file an ANDA too early, the FDA will reject it. They’ll have to wait. And waiting six months can mean losing market share to competitors who planned better. Some companies even time their filings to hit the exact day after exclusivity ends-down to the calendar day. A delay of just one day can cost millions.It’s not a loophole. It’s the law.

Some call pediatric exclusivity a loophole. But it’s not. Congress created it on purpose. The goal was to make sure kids get safe, properly studied medicines. And it worked. Since 1997, hundreds of drugs have been studied in children because of this rule. Pediatric labeling now exists for most common medications. The six-month extension isn’t a gift. It’s a trade: more data for kids, in exchange for a little more time without competition. And for drugmakers, it’s become one of the most valuable tools in their lifecycle strategy. It’s not about cheating the system. It’s about playing by the rules-and using them to protect their investment while improving patient care.What’s next?

The FDA continues to update its guidance on pediatric exclusivity. In 2023, they clarified how exclusivity applies to combination drugs and complex formulations. They’ve also started asking for studies in younger age groups-infants and neonates-more often. That means the rules are evolving, and companies need to stay ahead. For now, pediatric exclusivity remains a quiet but powerful force in drug markets. It doesn’t make headlines like patent battles or price hikes. But it shapes when generics appear, how much revenue brand companies make, and ultimately, how quickly children get better access to safe, labeled medicines.Does pediatric exclusivity extend the actual patent term?

No. Pediatric exclusivity does not extend the patent term. It extends the period during which the FDA can’t approve generic versions of the drug. Even if the patent has expired, the FDA still blocks generic approval for six months if pediatric exclusivity is active.

Can a generic drug be approved during pediatric exclusivity?

Only under three conditions: (1) The brand company grants a waiver, (2) a court rules the patent is invalid or not infringed, or (3) the generic company wasn’t sued within 45 days of filing and gets a waiver. Without one of these, the FDA cannot approve the generic during the exclusivity period.

Does pediatric exclusivity apply to biologics?

No. Pediatric exclusivity only applies to small-molecule drugs regulated under the Hatch-Waxman Act. Biologics are governed by a different law (BPCIA), and patents don’t block biosimilar approvals the same way, so pediatric exclusivity doesn’t apply.

How does the FDA know when to apply pediatric exclusivity?

The FDA issues a Written Request asking the drugmaker to study the medicine in children. If the company completes the studies and submits acceptable reports, the FDA reviews them within 180 days. If the studies meet the requirements, pediatric exclusivity is granted and added to any existing patent or exclusivity in the Orange Book.

Does pediatric exclusivity apply to all forms of the same drug?

Yes. If a drug has multiple dosage forms-like tablets, liquids, or creams-all containing the same active ingredient, pediatric exclusivity applies to all of them. The studies only need to be done on one form, but the six-month delay covers every version of the drug.

What happens if the patent expires before pediatric exclusivity ends?

The exclusivity still stands. The FDA continues to block generic approval until the six-month period ends, even if the patent has already expired. The exclusivity becomes the only legal barrier preventing generic entry.

Is pediatric exclusivity worth it for drug companies?

Yes. For a top-selling drug, six months of exclusive sales can mean $200 million to $500 million in additional revenue. The cost of conducting pediatric studies is often far less than that. Many companies now plan pediatric studies as a core part of their commercial strategy, not just a regulatory requirement.

Can pediatric exclusivity be granted to a drug with no patent or exclusivity?

Rarely. Normally, the drug must have at least nine months of existing exclusivity or patent life. But if a company applies to expand the drug’s use to children and needs new clinical data to get approval, the FDA can grant pediatric exclusivity even if no other protection exists.

Trevor Whipple

January 14, 2026 AT 03:44yo so ped exclusivity is just a fancy way for big pharma to stretch their monopoly? like bro the patent’s dead but the FDA still plays gatekeeper? that’s not regulation, that’s corporate extortion with a side of ‘we care about kids’ lol. i’ve seen kids on meds with zero pediatric data-so who’s really being protected here?

Lethabo Phalafala

January 15, 2026 AT 20:58Let me tell you something-this isn’t just about money. I’ve sat in pediatric wards where doctors had to guess doses because there were no studies. I’ve held babies on off-label meds that could’ve killed them. This rule? It forced companies to finally do the right thing. Yes, they get six months. But kids got safety. And that’s worth more than any profit margin.

Lance Nickie

January 16, 2026 AT 10:43patents r dead but exclusivity still blocks generics? sounds like a loophole. also why do they even call it ‘pediatric’? they just wanna delay generics. end of story.

Milla Masliy

January 17, 2026 AT 13:38As someone who grew up in a country where kids get whatever adult meds are left over, I can’t help but feel proud that the U.S. actually tried to fix this. Yeah, pharma profits from it-but look at the data now. We have actual dosing guidelines for kids on ADHD meds, antibiotics, even chemo. That didn’t exist in the 90s. This isn’t perfect, but it’s progress. And progress matters.

Damario Brown

January 19, 2026 AT 02:13so let me get this straight-big pharma gets a free 6-month monopoly just for doing the bare minimum? and the FDA lets them? this is why healthcare is broken. they don’t even have to prove it’s better for kids, just that they did the study. meanwhile, families pay $500 for a 30-day script because the generic can’t come in. and you call this ‘incentive’? it’s a tax on sick children. and the worst part? the studies are often just rehashing adult data with smaller pills. no real innovation. just regulatory gaming.

sam abas

January 20, 2026 AT 00:41Look, I’ve read the Orange Book. I’ve tracked ANDA filings. I’ve watched generic companies get rejected because they didn’t realize pediatric exclusivity was tacked onto a 2003 NCE. This isn’t some obscure footnote-it’s a multi-billion dollar chess game. And the worst part? Most people don’t even know it exists. The FDA doesn’t advertise it. The media ignores it. But if you’re in the biz, you know: the real patent clock doesn’t start until the exclusivity ends. And if you file even one day early? Your ANDA gets tossed. No appeal. No second chance. Just a six-month wait that costs you millions in lost revenue. And for what? So a company can sell a syrup version of a drug they already made a tablet for? The math is insane. One study. Six months. Three dosage forms. One drug family. That’s a 300% ROI on research costs. This isn’t innovation policy-it’s monopoly engineering disguised as child safety. And nobody’s talking about it because the people who benefit are the ones writing the rules.

John Pope

January 21, 2026 AT 23:24There’s a deeper metaphysical layer here, y’all. Pediatric exclusivity isn’t just a regulatory tool-it’s a mirror of our collective moral cowardice. We say we care about children, but we won’t pay for real pediatric R&D. So we invent a system where we reward the *appearance* of care, not the substance. The drugmakers? They’re not villains. They’re just playing the game we designed. We created a world where ‘doing the minimum to qualify’ is celebrated as ‘doing the right thing.’ And now we’re shocked when capitalism thrives within that structure? Wake up. The real tragedy isn’t the six-month delay-it’s that we’ve normalized ethical theater as policy. We’re not protecting kids. We’re protecting our own illusions of virtue.

Clay .Haeber

January 23, 2026 AT 11:39Oh wow, so the FDA is basically handing out VIP passes to Big Pharma like it’s a club night and the bouncer’s on payroll? ‘Oh honey, your patent expired? No worries-here’s a free six-month VIP lounge where generics can’t even peek through the window.’ And you call this ‘science’? Please. It’s corporate welfare with a pediatric-themed glitter sticker slapped on it. Next they’ll give us ‘senior exclusivity’ so we can keep paying $800 for insulin. Bravo. Someone get this man a Nobel Prize in cynicism.

Priyanka Kumari

January 24, 2026 AT 02:41I come from a place where pediatric meds are often unavailable or untested. So I see this differently. Yes, the system isn’t perfect-but it’s the first time in history that drug companies were *required* to study children. Before this, kids were just small adults on trial. Now? We have actual data. We have safer doses. We have labels that say ‘for children 2–11.’ That’s huge. The six-month delay? It’s a trade. And honestly? I’d rather pay a little more for a drug that’s been studied for my child than risk giving them something untested. This isn’t about profit. It’s about dignity.

Avneet Singh

January 24, 2026 AT 15:34Let’s be real-this is a textbook example of regulatory capture. The FDA’s own guidance documents are written by pharma lobbyists. The ‘written requests’? They’re often vague, low-effort, and designed to be easily met. The real cost of pediatric studies? A fraction of the revenue gained. This isn’t science. It’s a bureaucratic shell game. And the fact that people still call this ‘progress’ just proves how deeply we’ve internalized corporate propaganda. If you think this is about kids, you’re not paying attention.