When a new drug hits the market, it doesn’t just come with a price tag-it comes with a legal shield. Two types of protection keep generics off the shelves: patent exclusivity and market exclusivity. They sound similar, but they’re not the same. And confusing them can cost companies millions-or patients billions.

Patent Exclusivity: The Legal Lock

A patent is a government-granted right that says, "You can’t make, sell, or use this invention without my permission." In pharma, that invention might be the chemical formula, how it’s made, or how it’s used to treat a disease. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) gives this right for 20 years from the day the patent is filed.

But here’s the catch: drug development takes 10 to 15 years. By the time the FDA approves the drug, half the patent life is already gone. That’s why companies get extra time. If the FDA took too long to approve the drug, the patent can be extended through something called Patent Term Extension (PTE). The law caps this at 5 extra years, and the total market life can’t go beyond 14 years after approval.

Patents are also tricky because they come in layers. A composition of matter patent-protecting the actual molecule-is the strongest. But many companies file secondary patents: for new dosages, delivery methods, or uses. These are easier to get, harder to challenge, and often keep generics out even after the main patent expires. In fact, 68% of patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book are secondary, not core.

Market Exclusivity: The FDA’s Gate

Market exclusivity has nothing to do with patents. It’s a separate rule made by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Even if a drug has no patent, the FDA can still block generics for a set number of years. This isn’t about invention-it’s about data.

When a company develops a new drug, it spends years running clinical trials. The FDA reviews that data to decide if the drug is safe and effective. Market exclusivity says: "You can’t approve a generic version that copies this data for X years." It doesn’t matter if someone else figures out the same formula. If they want to use the innovator’s clinical data to get approval, they have to wait.

There are different types of market exclusivity:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE): 5 years of protection. No generic can even submit an application during this time.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity: 7 years for drugs treating rare diseases (fewer than 200,000 patients in the U.S.). Even if the drug isn’t patented, no one else can get approval.

- 儿科独占 (Pediatric Exclusivity): An extra 6 months added to any existing patent or exclusivity if the company studies the drug in children.

- Biologics Exclusivity: 12 years for complex drugs made from living cells-like insulin or cancer antibodies.

- 180-Day Exclusivity: The first generic company to challenge a patent gets a 6-month head start over all other generics.

These rules are enforced by the FDA automatically. You don’t sue. You don’t file a lawsuit. The FDA just won’t approve a copycat drug until the clock runs out.

The Real Difference: Who Controls What?

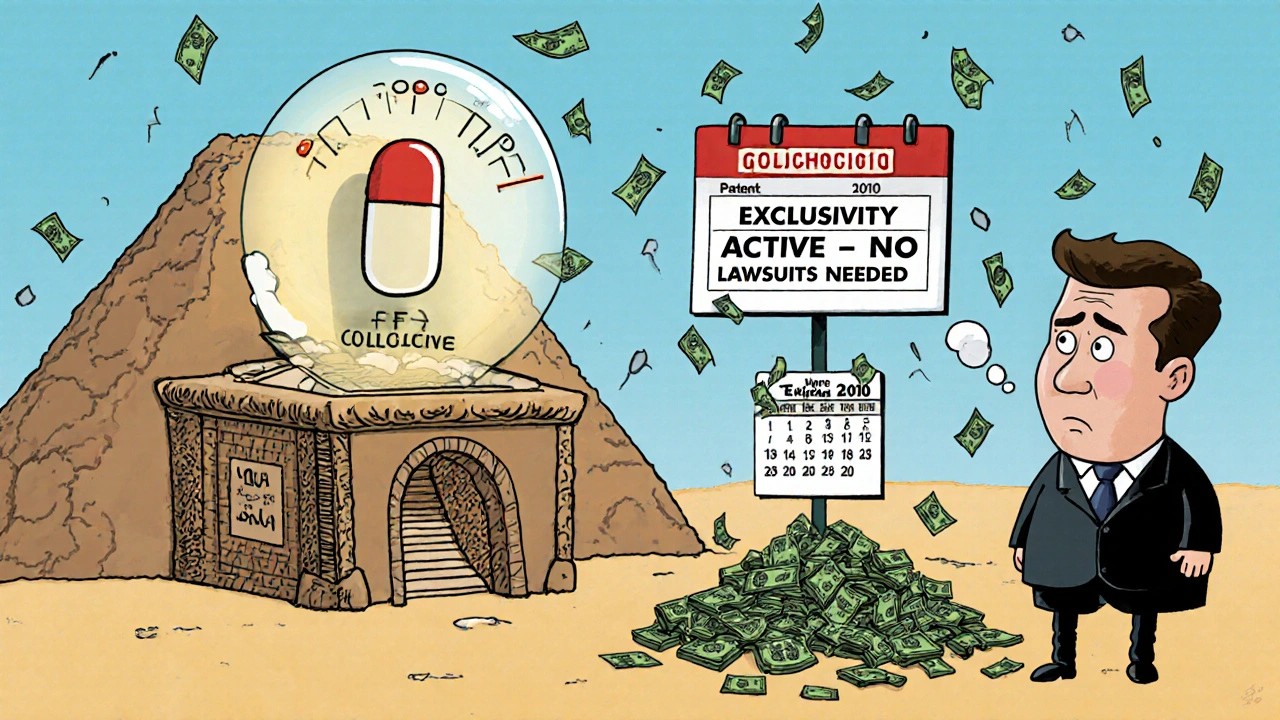

Patents are enforced by courts. If a generic company makes your drug, you sue them. It’s expensive, slow, and uncertain. Market exclusivity? The FDA just says no. No lawsuit needed. No judge. Just a bureaucratic block.

Here’s a real example: colchicine. It’s been used since ancient Egypt to treat gout. No one owned a patent on it. But in 2010, Mutual Pharmaceutical got FDA approval for a new formulation-and got 10 years of market exclusivity. Overnight, the price jumped from 10 cents per pill to nearly $5. The patent? Expired. The exclusivity? Still active.

Another case: Trintellix, an antidepressant. Its patents expired in 2021. But the FDA had granted 3 years of market exclusivity. So even though the patent was gone, generics couldn’t enter until 2024. Teva Pharmaceuticals lost an estimated $320 million because they assumed patents were the only barrier.

Who Gets What? The Numbers Don’t Lie

The FDA analyzed all approved drugs between 2018 and 2022 and found:

- 27.8% had both patent and market exclusivity

- 38.4% had patents only

- 5.2% had market exclusivity only

- 28.6% had neither

That last group? They’re the ones generics hit fastest. But the 5.2% with exclusivity only? They’re the silent blockers. Even without a patent, they kept generics out for years.

Small biotech firms rely heavily on exclusivity. In fact, 73% of small companies say regulatory exclusivity is their main protection-not patents. Especially for reformulated drugs or biologics, where patents are weak or nonexistent.

Why It Matters for Prices and Access

Drug development costs $2.3 billion on average. The first year after approval brings in 65% of the drug’s total lifetime revenue. That’s why companies fight to stretch exclusivity as long as possible.

But here’s the problem: some exclusivity periods overlap. A drug might have 5 years of NCE exclusivity, 12 years of biologics protection, and 20 years of patent-some stretching past 25 years. That’s longer than most people work.

And the system is getting more complex. The FDA launched its Exclusivity Dashboard in September 2023 so anyone can track when exclusivity ends. Generic companies are using it to plan their entry months in advance. Meanwhile, the PREVAIL Act of 2023 is trying to cut biologics exclusivity from 12 to 10 years. That could save billions in drug costs.

What Happens When You Mix Them Up?

Companies make costly mistakes. A 2022 survey by the Biotechnology Innovation Organization found that 43% of small firms thought patent expiration meant generics could enter immediately. They didn’t realize market exclusivity was still active. That led to $1.7 million in avoidable costs per company-on average.

And the FDA found that 22% of innovator companies failed to claim all the exclusivity they were legally entitled to. That’s 1.3 years of potential protection left on the table per drug. That’s not just a paperwork error-it’s lost revenue.

For generic manufacturers, the challenge is even harder. Filing a Paragraph IV certification to challenge a patent costs $8.3 million on average. If you’re wrong, you lose everything. If you’re right, you get 180 days of exclusivity worth up to $500 million. It’s a high-stakes gamble.

What’s Next?

The U.S. system is under pressure. Critics say it’s designed to protect profits, not patients. The 2023 FDA initiative requires companies to give more detailed reasons for exclusivity claims-starting January 1, 2024. That means less room for vague claims.

And globally, things are shifting. The WTO’s waiver for COVID-19 vaccines opened the door to similar rules for other drugs. If other countries start limiting exclusivity, U.S. companies could lose markets.

For now, the dual system stays: patents protect inventions. Market exclusivity protects data. Both delay generics. Both raise prices. And both are legal-just not always fair.

If you’re a patient, understanding this helps explain why your prescription costs so much. If you’re in pharma, missing one of these protections could cost you millions. Either way, knowing the difference isn’t just technical-it’s life-changing.

Can a drug have market exclusivity without a patent?

Yes. Market exclusivity is granted by the FDA based on the data submitted for approval, not on whether a patent exists. For example, colchicine had no patent but received 10 years of market exclusivity after a new formulation was approved. Orphan drugs and biologics also often rely on exclusivity alone.

How long does market exclusivity last for a new drug?

It depends on the type of drug. A New Chemical Entity (NCE) gets 5 years. Orphan drugs get 7 years. Biologics get 12 years. Pediatric exclusivity adds 6 months to any existing protection. The 180-day exclusivity for first generic challengers is a special incentive, not a standard period.

Does patent extension mean the drug stays expensive longer?

Yes. Patent Term Extension (PTE) can add up to 5 years to a patent’s life, but only if the FDA’s review caused delays. The total market exclusivity can’t exceed 14 years after FDA approval. This means a drug might stay protected for 15-20 years total, keeping prices high well beyond what most people expect.

Why do generic companies care about the 180-day exclusivity?

The first generic company to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell their version. During that time, no other generic can enter. That window can generate $100 million to $500 million in extra revenue, making it a huge financial incentive to file a patent challenge-even if it costs $8 million to do so.

Can a drug lose its exclusivity early?

Yes, but only in rare cases. If the FDA finds fraud, false data, or failure to comply with regulatory requirements, exclusivity can be revoked. Otherwise, once granted, exclusivity runs its full course. Even if a patent is invalidated in court, market exclusivity remains unless the FDA takes action-which rarely happens.

Joseph Townsend

November 17, 2025 AT 05:34So let me get this straight-some company takes a 2000-year-old herb, tweaks the pill shape, and suddenly it’s $5 a tablet? That’s not innovation, that’s a legal heist. The FDA’s playing banker while patients bleed out. And don’t even get me started on how they call this ‘exclusivity’ like it’s a damn trophy.

Meanwhile, my grandma’s insulin costs more than her rent. We’re not protecting innovation-we’re protecting greed dressed up in lab coats.

Bill Machi

November 17, 2025 AT 08:55This entire system is a betrayal of American ingenuity. We built the most advanced pharmaceutical industry in the world, and now we’re letting bureaucrats and foreign generic manufacturers undermine it with regulatory loopholes. The 180-day window? That’s not a reward-it’s a subsidy for foreign copycats. If we don’t tighten this up, we’ll be importing our own medicines from China next.

Patents and exclusivity aren’t privileges-they’re national security assets. Letting them erode is economic treason.

Elia DOnald Maluleke

November 18, 2025 AT 17:18One cannot help but reflect upon the metaphysical weight of intellectual property in the context of human suffering. The patent, once a sacred covenant between the state and the innovator, has devolved into a transactional weapon wielded by corporate entities who mistake profit for progress.

Market exclusivity, though ostensibly a shield for data, functions as a gilded cage-locking away knowledge that could save lives, not because it is unearned, but because it is commodified. Is this not the tragedy of modernity? That we have the power to cure, yet choose to delay-because the ledger demands it.

Colchicine, a remedy from the Nile, now priced beyond the reach of the American working class. What does this say of our soul?

satya pradeep

November 20, 2025 AT 17:12Bro this is wild. I work in pharma analytics in India and trust me, the 180-day exclusivity is the holy grail. One company I tracked got $400M in 6 months just by filing a Paragraph IV cert. But here’s the kicker-most small firms don’t even know about pediatric exclusivity or orphan drug windows.

They think patent expiry = generics flood in. Nope. FDA’s still blocking. I’ve seen companies lose millions because their legal team slept on the FDA exclusivity dashboard. It’s not rocket science, it’s just paperwork you gotta obsess over.

Also, biologics 12-year clock? That’s a joke. Insulin’s been around since 1920s and still locked down. Fix this or we’re all gonna pay more forever.

Prem Hungry

November 21, 2025 AT 15:22Thank you for this detailed breakdown. Many of us in the industry, especially those from emerging economies, are often unaware of the layered nature of exclusivity protections. The distinction between patent and market exclusivity is not merely academic-it is the difference between market entry and financial ruin.

I urge all aspiring generics manufacturers to study the FDA’s Orange Book and Exclusivity Dashboard religiously. One missed filing or misunderstood clause can cost you millions. This is not just law-it is survival.

Knowledge is power, and in this field, power translates to lives saved or lost.

Leslie Douglas-Churchwell

November 22, 2025 AT 07:09Okay but… what if this is ALL a psyop? 🤔

Big Pharma + FDA + Congress = The Triad of Profit. They created this whole ‘exclusivity’ maze so we’d think it’s ‘fair’ while they milk every dollar. Did you know the same CEOs who lobby for 12-year biologics exclusivity also donate to politicians who block Medicare negotiation? 🧠

And don’t get me started on the 180-day window-sounds like a rigged casino. First to file wins? More like first to bribe the lawyers.

They’re not protecting innovation. They’re protecting the illusion of it. 🚨💸 #PharmaConspiracy

shubham seth

November 22, 2025 AT 19:39Let’s be real-the entire system is a clown show. Companies file 20 patents on a single drug just to keep generics out. One patent for the molecule, one for the color of the pill, one for the shape of the tablet, one for ‘using it on Tuesdays.’

And the FDA? They just rubber-stamp it. Why? Because they’re underfunded and overworked. Meanwhile, patients are stuck paying $1000/month for a drug that costs $2 to make.

It’s not capitalism. It’s feudalism with a pharmacy license.

Kathryn Ware

November 23, 2025 AT 03:41I work in clinical trials and this post hit home. The 6-month pediatric exclusivity extension? It’s not just a loophole-it’s a lifeline. I’ve seen kids with rare diseases who only got treatment because a company invested in pediatric studies just to get that extra half-year. It’s not perfect, but it’s the only incentive they have to research conditions no one else cares about.

And yes, the 12-year biologics window is long-but those drugs are insanely complex. You can’t just reverse-engineer a monoclonal antibody like you can a pill. The manufacturing process alone takes years to replicate.

Let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater. We need reform, not revolution. Maybe cap exclusivity at 10 years for biologics, but keep the pediatric push. It saves lives. 🤝💙

kora ortiz

November 24, 2025 AT 20:21Jeremy Hernandez

November 25, 2025 AT 01:43Everyone’s acting like this is some new scandal. Nah. This has been going on since the 90s. The FDA lets companies game the system because they’re too scared to say no. And the public? They’re too busy scrolling TikTok to care.

Colchicine? $5 a pill? That’s not a drug-it’s a scam. And the fact that 43% of pharma companies don’t even know the difference between patent and exclusivity? That’s not ignorance. That’s negligence.

Someone’s making billions. Someone’s dying. And the rest of us are just yelling into the void.

Tarryne Rolle

November 25, 2025 AT 06:51What if the real issue isn’t exclusivity-but the assumption that drugs should be proprietary at all? Medicine is a public good. Knowledge should be shared. If we treated health like we treat public roads or fire departments, we wouldn’t be having this conversation.

Instead, we’ve built a cathedral of patents and regulatory delays, worshipping at the altar of shareholder value. And the faithful? They chant ‘innovation’ while their neighbors can’t afford insulin.

Perhaps the real question isn’t how long exclusivity lasts-but why we ever allowed it to exist.

Kyle Swatt

November 26, 2025 AT 15:46There’s a quiet truth here that no one wants to say out loud: the drug industry doesn’t innovate to cure. It innovates to extend. The real breakthrough isn’t the molecule-it’s the legal strategy.

That’s why you see 68% of patents in the Orange Book being secondary. It’s not science. It’s chess. And the board is rigged.

But here’s the thing-this isn’t about right or wrong. It’s about power. Who controls access to healing? Corporations? Regulators? Or the people who need it?

I don’t have an answer. But I know this: when a child cries because their medicine costs more than their school lunch, no amount of legal nuance justifies it.

Joseph Peel

November 26, 2025 AT 20:32As someone who has worked with international regulatory bodies, I can confirm that the U.S. system is uniquely complex. In the EU, market exclusivity is more transparent and less layered. In Japan, patent extensions are strictly limited. Here? It’s a patchwork of incentives, loopholes, and lobbying.

That said, the Exclusivity Dashboard is a step in the right direction. Transparency is the first antidote to abuse. But real reform requires political will-and that is in short supply.

For now, the only thing keeping this from collapsing is the sheer inertia of bureaucracy. And that’s not a system. That’s a waiting game.