What Parkinson’s Disease Really Does to Your Body

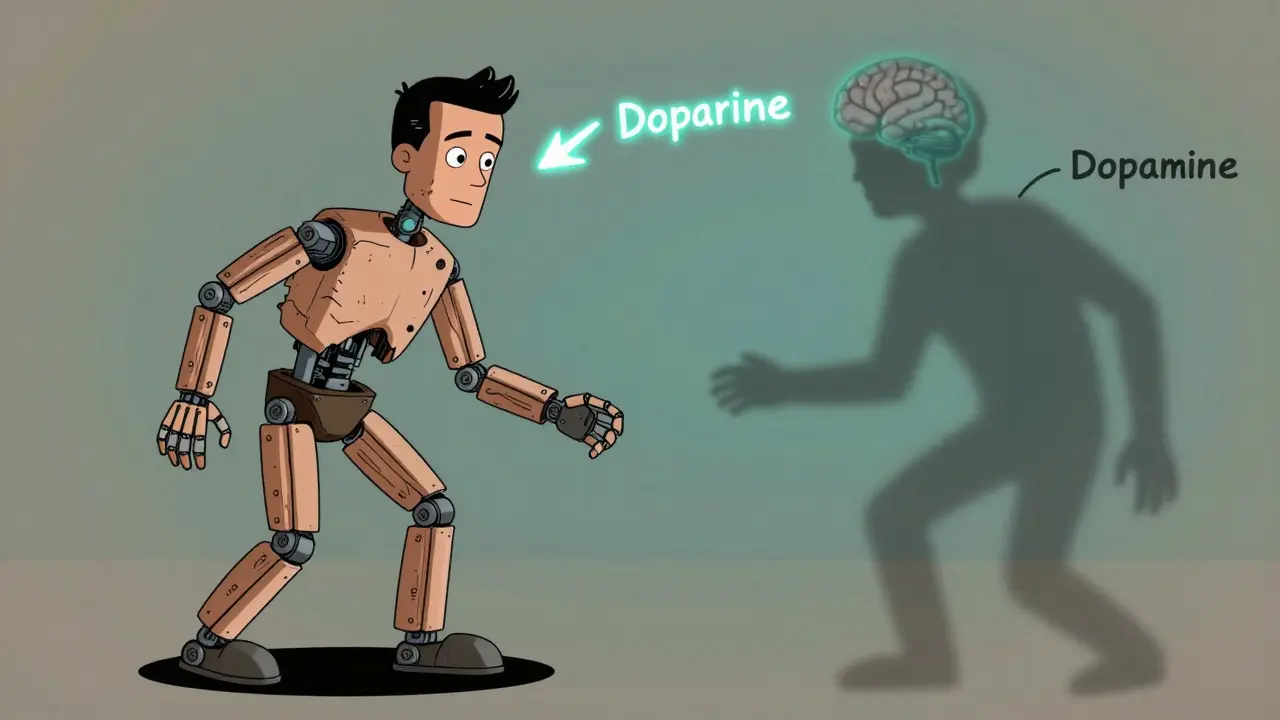

Parkinson’s disease isn’t just about shaking hands. It’s a slow, silent thief that steals movement, voice, balance, and sometimes even the ability to swallow or sleep. It starts with something small - a hand that doesn’t swing when you walk, a voice that gets quieter over time, or buttons that suddenly feel impossible to fasten. By the time most people realize what’s happening, the disease has already been working for years. The root cause? The brain is losing dopamine-producing neurons in a region called the substantia nigra. The substantia nigra is a cluster of nerve cells in the midbrain that produces dopamine, a chemical essential for smooth, coordinated muscle movement. When dopamine drops below a critical level, movement becomes stiff, slow, and unpredictable.

It’s not something you catch. It’s not caused by bad habits or diet. It’s a neurodegenerative condition, meaning nerve cells break down over time. About 60,000 Americans are diagnosed each year, mostly after age 60. But 1 in 25 cases shows up before 50 - that’s young-onset Parkinson’s. And while it’s not fatal on its own, complications like pneumonia from swallowing problems can be deadly. About 70% of deaths in advanced Parkinson’s are linked to breathing infections.

The Four Core Motor Symptoms You Can’t Ignore

Doctors don’t need fancy scans to diagnose Parkinson’s. They look for four key signs - and you only need two to start the process. The first and most recognizable is resting tremor. A resting tremor in Parkinson’s is a rhythmic shaking that happens when the hand, arm, or leg is relaxed, often described as a "pill-rolling" motion between the thumb and finger. It usually starts on one side only. About 70% of people notice this first. But here’s the twist: 20-30% of patients never develop a tremor at all. So if you don’t shake, it doesn’t mean you’re safe.

The second symptom is rigidity. Rigidity means your muscles feel stiff and resist movement, even when someone else tries to move your arm or leg. It can feel like bending a rusty hinge. There are two types: "lead-pipe" - constant resistance - and "cogwheel" - a jerky, ratchet-like feel. About 85% of patients have the cogwheel version. You might notice it when your arm feels heavy lifting groceries or when your neck won’t turn easily.

The third, and most important, is bradykinesia. Bradykinesia means slow movement - not just slow, but painfully delayed and effortful. It’s the one symptom that shows up in nearly every patient. It makes simple things take forever: getting out of bed, tying shoes, writing your name. Your face may freeze into a blank mask. You blink less. Your voice fades to a whisper. Handwriting shrinks into tiny, cramped letters - a sign called micrographia. Studies show dressing takes 2.3 times longer. Buttoning a shirt? Nearly three times longer.

The fourth is postural instability. Postural instability is trouble with balance - not from dizziness, but from your body’s inability to adjust quickly when you lean or turn. This usually shows up later, after five to ten years. It’s why people with Parkinson’s fall so often. About 68% fall at least once a year. One in three falls repeatedly. You might not notice it until you’re already tumbling.

Other Motor Signs That Sneak Up on You

There’s more than just the big four. Dystonia. Dystonia is when muscles contract involuntarily, causing twisting or abnormal postures - like a foot turning inward or your neck pulling to one side. It’s more common in younger patients and can be one of the earliest signs. You might wake up with a curled toe that hurts to straighten.

Walking changes, too. Your arms stop swinging. Your steps get shorter - up to 35% shorter. You shuffle. Your speed drops by 30-40%. You might freeze in place when turning or walking through doorways. This isn’t just inconvenient - it’s dangerous. Falls are the leading cause of injury.

Speech gets quiet and slurred. Voice volume drops 5-10 decibels - enough to make you hard to hear in a noisy room. About 89% of people develop a soft voice. Swallowing becomes harder. Saliva builds up because you don’t swallow often enough - that’s why drooling happens in half to 80% of cases. In advanced stages, 80% struggle to swallow food safely, putting them at risk for choking or pneumonia.

How Medications Work - and Where They Fall Short

The main goal of treatment? Replace the dopamine your brain is losing. The gold standard is levodopa. Levodopa is a chemical that the brain converts into dopamine, helping restore movement control. It’s been used since 1967 and still works for 70-80% of people in the early years. But it doesn’t last forever. After five years, about half of patients start having "on-off" fluctuations - sudden switches between being able to move and being frozen. They also develop dyskinesias. Dyskinesias are involuntary, writhing movements - often in the arms, legs, or head - caused by long-term levodopa use.

That’s why younger patients often start with dopamine agonists. Dopamine agonists like pramipexole and ropinirole mimic dopamine in the brain without turning into it. They’re less powerful than levodopa but have fewer long-term side effects. They help 50-60% of early-stage patients. But they come with their own problems: dizziness, sleep attacks, and sometimes compulsive behaviors like gambling or overeating.

After ten years, about 30% of patients become candidates for deep brain stimulation (DBS). Deep brain stimulation is a surgical procedure where electrodes are implanted in the brain to send electrical pulses that regulate abnormal signals. It doesn’t cure Parkinson’s, but it can smooth out the "on-off" swings and reduce dyskinesias. It’s not for everyone - you need to be in good health, have clear symptoms that respond to levodopa, and not have dementia.

Daily Life in the Grip of Parkinson’s

Imagine trying to get dressed when your fingers won’t cooperate. Or standing up from the couch and feeling like your legs are stuck. Or realizing your partner has to repeat themselves because your voice is too soft. These aren’t "annoyances" - they’re daily battles.

Turning over in bed becomes a chore. About 65% of people report this within five years. Getting out of bed takes effort. Sitting up? A process. Many people need help just to roll over.

Sexual function often drops. In men, 50-80% report reduced desire, erection problems, or difficulty reaching orgasm. It’s rarely discussed, but it’s real. Medications can help, but so can honest conversations with a partner or a doctor.

Even sleep gets ruined. Some people have akathisia. Akathisia is an inner restlessness - the urge to move constantly, even when tired. It affects 15-25% of patients and makes falling asleep nearly impossible. Others have vivid dreams or act out their dreams - a condition called REM sleep behavior disorder. It can show up years before movement problems.

And then there’s the emotional toll. Depression affects nearly half of people with Parkinson’s. Anxiety is common. The fear of falling, of losing independence, of being a burden - it wears you down. It’s not just the physical symptoms. It’s the grief for the life you thought you’d have.

What Actually Helps Beyond Pills

Medications keep you moving, but they don’t stop the decline. The real power lies in movement itself. Physical therapy isn’t optional - it’s essential. A 12-week program of targeted exercise can improve walking speed by 15-20% and cut fall risk by 30%. Tai chi, dance, and boxing classes designed for Parkinson’s have shown real results. One study found that people who danced twice a week had better balance and fewer falls than those who didn’t.

Speech therapy helps too. If your voice is fading, a speech pathologist can teach you to project, breathe deeper, and speak louder. It’s not magic - it’s training. And swallowing therapy can reduce the risk of choking and pneumonia.

Occupational therapy makes daily life easier. Adaptive tools - button hooks, weighted utensils, non-slip mats - aren’t gimmicks. They’re lifelines. A simple shower chair can mean the difference between staying independent and needing full-time care.

And don’t underestimate the power of routine. Keeping a schedule - meals, meds, walks, sleep - gives your brain predictability. Parkinson’s thrives on chaos. Structure fights back.

Where We Are Now - And What’s Coming

Right now, no drug can stop Parkinson’s from progressing. Every treatment is about managing symptoms. But research is moving fast. Scientists are testing drugs that target alpha-synuclein. Alpha-synuclein is a protein that clumps together in the brains of people with Parkinson’s, forming toxic structures called Lewy bodies. If we can clear these clumps early, we might slow or even stop the disease.

Genetic testing is becoming more common, especially for young-onset cases. Some forms of Parkinson’s are linked to specific genes. Knowing your risk can help with early planning - and future participation in clinical trials.

Wearable sensors are starting to appear in clinics. They track your steps, tremors, and freezing episodes in real time. This isn’t science fiction - it’s already helping doctors adjust meds more precisely.

The goal isn’t a cure tomorrow. It’s more good days. More independence. More time to hold your grandchild’s hand, to walk in the park, to speak without straining. That’s what matters.

Is Parkinson’s disease hereditary?

Most cases aren’t inherited. Only about 10-15% of people with Parkinson’s have a clear family history. But certain gene mutations, like LRRK2 or GBA, can increase risk. If you’re diagnosed under 50 and have relatives with Parkinson’s, genetic counseling may be helpful - but it’s not necessary for everyone.

Can exercise really make a difference?

Yes - and not just a little. Studies show regular, intense exercise improves mobility, balance, and even mood. Activities like brisk walking, cycling, tai chi, and dance have all been proven to slow functional decline. One trial found that people who exercised 2.5 hours a week delayed the need for higher medication doses by nearly two years. Movement isn’t just therapy - it’s medicine.

Why does levodopa stop working after a few years?

Levodopa doesn’t stop working - your brain changes. As more dopamine cells die, your brain loses its ability to store and release dopamine steadily. This leads to "on-off" periods where the drug’s effect wears off quickly. It also causes dyskinesias because the brain becomes oversensitive to dopamine spikes. Adjusting timing, adding other meds, or switching to DBS can help manage this.

Does everyone with Parkinson’s get dementia?

No. About 50-80% of people with Parkinson’s develop some cognitive changes after 10 years, but not all progress to full dementia. Memory issues, slow thinking, or trouble finding words are common. True dementia - where you lose the ability to live independently - affects about 30-40% after 15-20 years. Medications and lifestyle can delay this.

What should I do if I think I have Parkinson’s?

See a neurologist who specializes in movement disorders. General doctors often miss early signs. Don’t wait for tremors - if you notice slow movement, stiff muscles, or changes in your walk, voice, or handwriting, get checked. Early diagnosis means earlier support - physical therapy, lifestyle changes, and medication timing that can preserve your independence for years longer.

Final Thoughts: It’s Not Just About the Shaking

Parkinson’s doesn’t announce itself with a bang. It whispers. A slower step. A quieter voice. A missed button. But once you see it, you see it everywhere. The truth is, no pill will ever give back what’s lost. But movement, connection, and smart support can give you back your life - piece by piece, day by day. You don’t have to wait for a cure to live well. You just have to start moving - and keep going.

Siobhan K.

December 21, 2025 AT 18:59Brian Furnell

December 22, 2025 AT 03:48Christina Weber

December 23, 2025 AT 10:15Cara C

December 25, 2025 AT 01:36Erika Putri Aldana

December 26, 2025 AT 00:04Grace Rehman

December 27, 2025 AT 05:37Cameron Hoover

December 27, 2025 AT 06:03Jerry Peterson

December 27, 2025 AT 20:00Dan Adkins

December 28, 2025 AT 20:42Orlando Marquez Jr

December 30, 2025 AT 08:06Jay lawch

December 31, 2025 AT 01:15Michael Ochieng

December 31, 2025 AT 12:32