Mar 7, 2010

cost of cancer treatment $618,616 – Amanda Bennet’s story

After 2 years of her husband’s death Amanda Bennet examines the cost of keeping one man alive suffering from cancer.

After 2 years of her husband’s death Amanda Bennet examines the cost of keeping one man alive suffering from cancer.

It was sometime after midnight on Dec. 8, 2007, when Dr. Eric Goren told me my husband might not live till morning. The kidney cancer that had metastasized almost six years earlier was growing in his lungs. He was in intensive care at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and had begun to spit blood.

Terence Bryan Foley, 67 years old, my husband of 20 years, father of our two teenagers, a Chinese historian who earned his PhD in his sixties, a man who played more than 15 musical instruments and spoke six languages, a San Francisco cable car conductor and sports photographer, an expert on dairy cattle and swine nutrition, film noir, and Dixieland jazz, was confused. He knew his name, but not the year. He wanted a Coke.

Should Terence begin to hemorrhage, the doctor asked, what should he do?

This was our third end-of-life warning in seven years. We had fought off the others, so perhaps we could dodge this one, too. Terence’s oncologist and I both believed that a new medicine he had just begun taking, Pfizer’s (PFE) Sutent, would buy him more life.

Keep him alive if you can, I said.

Terence died six days later, on Friday, Dec. 14.

What I couldn’t know then was that the thinking behind my request—along with hundreds of decisions we made over the years—was a window on the impossible calculus at the core of today’s health-care dilemma. Terence and I were eager to beat his cancer. Backed by robust medical insurance provided by a succession of my corporate employers, we were able to wage a fierce battle. As we made our way through a series of expensive last chances, like the one I asked for that night, we didn’t have to think about money, allocation of medical resources, the struggles of roughly 46 million uninsured Americans, or the impact on corporate bottom lines.

Terence’s treatment was expensive. The bills for his seven years of medical care totaled $618,616, almost two-thirds of which was for his final 24 months. Still, no one can say for sure if the treatments helped extend his life.

Over the final four days before hospice—two in intensive care, two in a cancer ward—our insurance was billed $43,711 for doctors, medicines, monitors, X-rays, and scans. Two years later the only thing I can see that the money bought for certain was confirmation he was dying. Along with a colleague, Charles Babcock, I spent months poring over almost 5,000 pages of documents collected from six hospitals, four insurers, Medicare, three oncologists, and a surgeon. Those papers tell the story of a system filled with people doing their best. Stepping back and looking at that large stack through a different lens, a string of complex questions emerges.

31% for Paperwork

Health-care costs represent 17% of today’s U.S. gross domestic product. Medicare devotes about a quarter of its budget to care in the last year of life, according to the policy journal Health Affairs. Yet as I fought to buy my husband more time, it didn’t matter to me that the hospital charged more than 12 times what Medicare then reimbursed for a chest scan. It also didn’t matter that UnitedHealthcare (UNH) reimbursed the hospital for 80% of the $3,232 price of a scan, while a few months later our new insurer, Empire BlueCross & BlueShield, paid 24% for the same test. And I didn’t have time to be thankful that the insurers negotiated the rates with the hospital so neither my employers nor I actually paid the difference between the sticker and discounted prices.

Looking at that stack of documents, it is easy to see why 31% of the money spent on health care went to paperwork and administration, according to research published in 2003 in the New England Journal of Medicine. That number has stayed the same or grown since then, says Dr. Steffie Woolhandler, a professor at Harvard Medical School and a co-author of the study. Often Terence’s bills, with their blizzard of codes, took days to decipher. What did “opd patins t” or “bal xfr ded” mean? Was the dose charged the same as the dose prescribed?

The documents revealed an economic system in which the sellers don’t set the prices and the buyers don’t know what they are. Prices bear little relation to demand or how well goods and services work. “No other nation would allow a health system to be run the way we do it. It’s completely insane,” said Uwe E. Reinhardt, a political economy professor at Princeton University who has advised Congress, the Veteran’s Administration, and other federal agencies on health-care economics.

In reviewing Terence’s records, we found Presbyterian Medical Center in Philadelphia charged UnitedHealthcare $8,120 in 2006 for a 350 mg dose of the drug Avastin, which should have been free as part of a clinical trial. When my Bloomberg colleague inquired, the 80% insurance payment was refunded. A small mixup, but telling.

Some drugs Terence took probably did him no good. At least one helped fewer than 10% of patients. Today, pharmaceutical companies and government agencies are trying to sort out the economics of developing drugs that will help only a small subset of patients. These drugs are very expensive. Should every patient have the right to them?

Terence and I answered yes. Each drug potentially added life. Yet that, too, led me to a question I still can’t answer. When is it time to quit? Congress dodged the question last year as it tried to craft a health-care bill. The mere hint of limiting the ability to choose care created a whirlwind of accusations of “death panels.”

One thing I know is that I don’t envy the policymakers. As the health-care debate heated up, I remembered the fat sheaf of insurance statements that had piled up after Terence’s death. Our children, Terry, 21, and Georgia, 15, assented to my idea of gathering every record to examine what they would show about end-of-life care—its science, emotions, and costs. Terence would have approved.

Taking it all into account, the data showed we had made a bargain that hardly any economist looking solely at the numbers would say made sense.

Why did we do it? I was one big reason. Not me alone, of course. The system has a strong bias toward action. My husband, too, was unusual, said Keith Flaherty, his oncologist, in his passionate willingness to endure discomfort for a chance to see his daughter grow from a child to a young woman, and his son graduate from high school.

After Terence died, Flaherty drew me a picture of a bell curve, showing the range of survival times for people with kidney cancer. Terence was way off in the tail on the right-hand side, an indication he had beaten the odds. For many, an explosion of research and drug discoveries had made it possible to daisy-chain treatments and extend lives for years—enough time to keep our quest from having been total madness.

Terence used to tell a story, almost certainly apocryphal, about his Uncle Bob. Climbing aboard a landing craft before the invasion of Normandy, Bob’s sergeant was said to have told the men that by the end of the day, 9 out of 10 of them would be dead. Said Bob: “Each one of us looked around and felt so sorry for those other nine poor sonsabitches.”

For me, it was about pushing the bell curve. Knowing there was something to be done, we couldn’t not do it. Believing beyond logic that we were going to escape the fate of those other poor sonsabitches.

It is hard to put a price on that kind of hope.

A shadow but good odds

We found the cancer by accident, on Sunday, Nov. 5, 2000, in Portland, Ore. Terry had invited a dozen friends for a sleepover to celebrate his 12th birthday. I was making pancakes and shipping the boys home. Terence had been having stomach cramps for weeks. Suddenly he was lying on the bed, doubled over in pain. Our family doctor ordered him to the emergency room.

We were immediately triaged through. Not a good sign, I thought. The kids sat on the waiting-room floor, Barbies and X-Men around them, while Terence writhed in a curtained alcove. When he returned from a scan, the doctor said, almost as an aside: There’s a shadow on his kidney. When he’s feeling better, you should take a look at it. Both of us were annoyed. Why would we think about a shadow on his kidney? That wasn’t the problem. He was in such pain he could barely breathe.

The cause of the pain turned out to be violent ulcerative colitis. The damaged colon was removed on Dec. 13, in an operation that left Terence so weak that he spent three weeks, including Christmas morning, immobile in a chair. Colleagues delivered meals to the house. My sister wrapped presents. My boss sent over her husband to put up our lights. I felt so bad for Terence that I got him a cat, the pet he had long wanted. The orange kitten howled in a box under the tree.

And the shadow? We were so grateful he was out of pain that we would have ignored it had someone from the hospital not called to urge us to find out what it meant. Within a month, Terence was in surgery again. On Jan. 18, Dr. Craig Turner removed the diseased kidney. Emerging from the five-hour operation, Turner confirmed the worst: He believed the shadow was cancer. A week later, when Terence was well enough to walk into the doctor’s office, Turner was reassuring.

“We got it all,” he said.

Terence teared up. “Thank you for saving my life.”

The bills from Regence BlueCross BlueShield of Oregon show the operation was relatively inexpensive, just over $25,000, about 4% of the eventual total charged to keep Terence alive. Our share was $209.87. I never looked at or thought about the total cost, or the $14,084 that our insurance—in reality, my employer—paid. We never had to consider who was actually shouldering the bills.

Kidney cancer is uncommon, accounting for about 3% of all cancers, or about 50,000 new cases in the U.S. last year, according to the Kidney Cancer Assn. Terence was a typical patient: an older man, overweight, and an ex-smoker. Asymptomatic for a long time, most kidney cancers are discovered accidentally or too late. So we felt lucky. The first tool for fighting kidney cancer is usually the one used since medieval times: the knife, or its technological equivalent. If a tumor is removed early enough, before it flings microscopic cells into the bloodstream that can implant in other organs, surgery is close to a cure.

For Terence the odds looked good. His 7-centimeter tumor showed no signs of having spread. According to the traditional method of evaluating, or staging, the cancer, that meant he had an 85% chance of surviving five years. A lab report soon chilled our optimism. Tests on Terence’s tumor showed that he had so-called collecting duct cancer. Named for the part of the kidney where it is thought to originate, collecting duct is the rarest and most aggressive form of kidney cancer. In my online research, almost everyone who had it died within months, sometimes weeks, of diagnosis.

Most kidney cancers don’t respond well to chemotherapy. There was no accepted treatment after surgery. Almost nothing was known about collecting duct cancer. Only about 1% of kidney cancer patients receive that diagnosis. Dr. Turner and I could find just 50 cases documented in the medical literature worldwide, and nothing had proved effective in halting it. “Watchful waiting” was the recommended path.

Waiting for him to die was what we feared.

He didn’t die. He got better. We didn’t know why. We tried not to think about it.

By the spring of 2002, we had moved to Lexington, Ky., where I was the editor of the local newspaper and Terence was creating an Asia Center at the University of Kentucky. He seemed fine. He began moving Chinese and Japanese history books to his office. On Saturdays we drove through the bluegrass to take seven-year-old Georgia to riding lessons. We reluctantly let 13-year-old Terry crowd-surf at his first rock concert.

Then, on May 6, 2002, Terry called me at work, panic in his voice. “Mom, come home. Dad is very sick.”

His father was in bed, his face flaming with fever, shaking with chills under a pile of blankets. He could barely speak. “The cancer is in my lungs,” he said. “I’ve got six to nine months left.”

Fear, and internet plunge

He had been keeping that secret for months. In February, routine follow-up scans had spotted the cancer’s spread. “The first thing Terence said was, ‘Doc, do you have any female patients who have recently died? I need to find a widower so my wife can meet her next husband,’ ” his Lexington oncologist, Dr. Scott Pierce, later recalled. After more tests, Dr. Pierce prescribed Interleukin-2 because there were no other options. Injections of the protein, at $735 a dose, were intended to stimulate the immune response to help fight the cancer’s invasion. The overall response rate was only about 10%. For most patients, Interleukin-2 did absolutely nothing.

Terence hadn’t wanted to worry us. In his mind, if he recovered, we would never know how close he came; if he died, he would have spared us months of anguish. He started a diary and spent more time in the office so we would get used to his absence.

His secret was betrayed by his violent reaction to his first dose of IL-2. Suddenly his actions over the last several weeks made sense. He had been giving away musical instruments and pieces of art. “I have too much stuff,” he had told me, a bizarrely improbable statement coming from him. I was amused, exasperated, and touched by his desire to protect us. Even under the strain of his disease, he was so much himself. “Did you think I wouldn’t have noticed if you didn’t come home one day?” I asked.

I spent that night awake in our dark living room. For the first and only time, I felt pure terror. A few days later I visited a therapist.

“I can’t survive without him,” I said.

“What does he say when you feel this way?” she asked.

“He says I can handle anything.”

“You’ll need to say that to yourself.”

Terence stopped taking IL-2 after a few weeks of treatments, unable to stand the side effects.

I plunged into the Internet. If there were something out there that could save him, I was going to find it. Years before, one of my former colleagues, dying from AIDS, had suddenly come back to vigorous life because of a chance introduction to a doctor who prescribed what was then an experimental antiviral cocktail. Another had beaten leukemia with a cutting-edge bone marrow transplant. We could defeat this.

I downloaded papers, presentations to the Kidney Cancer Assn., abstracts from the National Library of Medicine. I called researchers and oncologists, pathologists and fellow journalists. When the research became overwhelming, I hired a retired nurse to help. My boss’s wife, a nurse herself, dug in too. After I messaged one couple about a clinical trial in Texas, they offered us their spare bedroom.

Throughout the spring and summer of 2002, Georgia, then 8, rode her bicycle up and down shady South Ashland Avenue. Thirteen-year-old Terry and his friends Shannon, Hughes, and Tanner came in last at their first battle of the bands. Terence sounded optimistic. “It’s my dream,” he said. “Some day we’re going to gig together.”

Awaiting scans, learning the violin

The truth was we were both shaken by the dire prognosis.

“What would you regret dying without having seen?” I asked. He answered without hesitation: “Pompeii.” We pulled Terry from his eighth-grade class, Georgia out of second, and flew to Italy to see the excavated remains of the city once buried under volcanic ash. We walked the cobbled streets, poked into frescoed houses, taverns, and baths, and took an eerie comfort from the 2,000-year-old shapes of families huddled together, trying to ward off disaster.

By then our research had led us to the Cleveland Clinic, where Dr. Ronald Bukowski had specialized in kidney cancer for over 20 years. At our first meeting, in August 2002, Terence explained that he had collecting duct cancer.

“No you don’t,” Bukowski said.

We were confused. How did he know?

“You’re sitting here,” he said. “If you had collecting duct, you would be dead.”

Bukowski argued that the disease was growing so slowly that we should simply watch and wait. We did, for three years. Then, in December 2005, a scan showed that the cancer in his lungs had begun to grow.

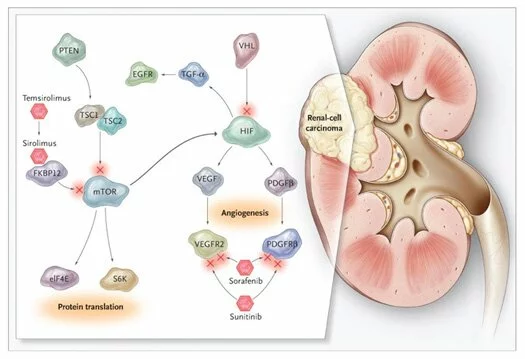

By this time, research had progressed. New drugs designed to attack a tumor’s blood supply were appearing to slow the growth of a wide range of cancers. Bukowski recommended we enter a clinical trial, pretty much the only way to get these targeted therapies. He referred us to Dr. Flaherty in Philadelphia, where we had moved in June 2003 when I changed jobs.

The drugs Flaherty was testing—Genentech’s Avastin and Bayer’s Nexavar—had showed promise individually. The trial would find out how they worked together. In March 2006, Terence took his first intravenous dose of Avastin, an hour-long process, and swallowed his first Nexavar. The side effects were hard. There were rashes, sometimes debilitating stomach pains. But he continued teaching, picking up the kids at school, studying and writing. He worked on his book, a grammar text based on classical Chinese poetry. He started to learn to play the violin and to read and write Arabic. Every two weeks he went for an Avastin drip. And every month we anxiously awaited the results of a chest scan.

At first the cancer didn’t budge. Then it began to retreat.

Because Terence was in a clinical trial, Genentech and Bayer provided their drugs free. I learned that over the years of Terence’s battle with cancer, some insurers drove harder bargains than others. In December 2006, for example, United Healthcare paid $2,586 to University of Pennsylvania Hospital for a chest scan; in March 2007, after I switched employers, Empire BlueCross paid $776 for the same $3,232 bill.

When it came to the insurance companies, the sticker price meant little since they had negotiated their own deals with the hospital. Neither the hospital nor the insurance companies would elaborate. The entire medical bill for seven years, in fact, was steeply discounted. The $618,616 was lowered to $254,176 when the insurers paid their share and imposed their discounts. The portion of the charges that were not covered for the most part vaporized. Terence and I were responsible for and paid $9,468—less than 4%.

During the trial, Terence packed boxes for the troops in Iraq and Afghanistan, loading them in our kitchen with deodorant, wet wipes, Mars bars, Kool-Aid, beef jerky, batteries, and magazines. A veteran of Naval Intelligence and the U.S. Air Force reserves, he walked almost every day to the post office with a box addressed to “Any Soldier.” Behind the counter, the smiling lady with the long red hair extensions became his friend, and every so often a soldier would drop him a thank-you note.

Life went on.

Then, in August 2007, from half a world away, I heard the cancer return.

I was on a business trip to China when Terence coughed during one of our phone calls. By the time I got home, scans had confirmed growth of one of the lung’s cancerous spots.

By now, more than six years had passed since we first saw the shadow, and I was used to the scares. Avastin’s side effects—fatigue, stomach ailments, rashes—had been getting him down, and the doctor had agreed back in May to let him stop treatments. So we’ll go back on the Avastin, I thought, or cut out or laser out the growth, add new treatments, and go on.

The records document our renewed fight. Terence resumed Avastin. Because he was no longer in a trial, our insurance company was billed $27,360 a dose, every two weeks, more than the cost of the kidney surgery in 2000. Empire BlueCross paid $6,566.40. We paid nothing. So who did the paying? The health insurance system depends on healthy people bearing the cost for sick ones like Terence. For all its incredible treatment benefits, the system is untenable. Should you have had a voice in Terence’s final days? Would I make the same decision with my money for your loved ones? These are things I think about now but can’t answer.

No consensus

He coughed almost continuously. His weight plunged. He needed help on the stairs. He began to use a cane. When his friend Woody came to visit, Terence couldn’t muster the breath to blow his cornet. He coughed and coughed and coughed. In the last week of October, he called me at work.

“I can’t pick Georgia up at school,” he said. “I can’t get out of the chair.” On Halloween, his Dracula costume stayed in the basement. We left the candy on the doorstep.

On Nov. 8 we saw Dr. Ali Musani, a pulmonologist specializing in cancer. We hoped that the growing tumor in Terence’s chest could be removed. Unable to stand or sit unassisted, he lay on the floor and refused to get up. Alarmed, Musani admitted him to the hospital. He said there was nothing he could do about the tumor. He gently mentioned that it might be time to consider hospice. We brushed off the suggestion.

Terence stayed in the hospital four days. Meanwhile a quiet tension was building. Flaherty and I believed this episode to be a temporary setback. Other doctors and nurses saw a patient near the end.

On Nov. 11, before discharging him, a doctor propped one of Terence’s scans on a light board so we could clearly see the blizzard of white spots, hundreds of tumors, covering his lungs.

Avastin wasn’t stopping them.

Flaherty was not fazed by the growth, and pointed out that many of the doctors looking at the scans didn’t understand the course of kidney cancer. He and I wanted to move on to the next link in the daisy chain of newly available drugs. Sutent, another targeted therapy, had been approved the year before. It worked as Avastin did, by stopping cancer’s ability to build extra blood vessels to feed its growth, but in a different way. One $200 pill a day. A shot at more life. Sutent might have more serious side effects—rashes, fatigue, stomach distress, strokes—but Terence was game. He began taking it on Nov. 15.

At home, he drew a line down the middle of a piece of paper. On one side he wrote things to throw away. On the other, things to keep.

“Stop that!” I snapped. “You aren’t going to die.”

I prepared for what I expected would be a new phase of our life. I found protein drinks online and protein bars in a bodybuilding shop. I got forms for a handicapped license plate, looked into outfitting our row house with a stair lift.

Terence was no longer able to get in and out of bed alone, so I hired a health aide. Whatever he craved, I bought. I wrote down everything he ate. Cold grapefruit slices. Chicken noodle soup. Clam chowder. I counted the calories he consumed one day: 210.

On Friday, Dec. 7, just as the aide was packing to leave for the day, Terence looked up, startled, as the corners of his mouth foamed bright red with blood. It was a struggle to get him down our narrow stairs to the ambulance. In the emergency room it was clear something was seriously wrong. “What’s your name?” asked the ER doctor. Terence responded correctly. “What’s the date?” Terence gave the doctor what the kids and I recognized as “Daddy’s ‘Just how dumb are you?’ ” look. But he couldn’t answer.

“Who’s the President of the United States?” That triggered something. “That moron, Bush,” he said.

Terence was admitted that night to a ward where Eric Goren was doing his last intensive-care overnight shift of a three-year residency. In a small break room, alongside vending machines selling soft drinks and chips, Goren told me that bleeding from the lungs might suddenly become uncontrollable. If that happened, what should he and his team do?

I wanted to see whether Flaherty still believed Sutent could make a difference, but I couldn’t reach him. Goren and I settled on what the hospital called Code-A. Do everything possible to prevent a major bleed or anything life-threatening. But don’t take heroic measures if death seems inevitable.

I called the children to the hospital.

My decision about Terence’s treatment, so hard on Saturday, was easy by Monday. The scans now were showing signs of cancer in his brain, surrounded by a cascade of hundreds of tiny strokes. I had Terence’s signed living will, but I didn’t need it. I knew what this man who lived for books, music, and ideas would want.

When Flaherty arrived, he looked shaken. “I didn’t expect this,” he said.

That afternoon I signed the papers transferring Terence to hospice. The next day the hospital staff took away the machines and the monitors. The oncologists and radiologists and lab technicians disappeared. Hospice nurses, social workers, chaplains, and counselors for me and the children—began to arrive and the focus shifted from treatment to easing our transition.

Over the next three days we were charged $14,022 for the same hospital bed. Included were the pain and anxiety medications Ativan and Dialaudid, his monitoring, and counseling for a different kind of pain management for me and the children. The bill was less than a third of the previous four days’ $43,711.

Terence drifted into a coma on Tuesday. I e-mailed his friends and read their goodbyes aloud, hoping he could hear and understand. I slept in a chair. At about 2:30 a.m. Friday, a noise in the hall startled me. I awoke just in time to hold his hand as he died.

They gave me back his wedding ring the next day.

Ten days later, the kids hung Daddy’s Christmas stocking alongside our three. I mailed the cards he had addressed months earlier, slipping in a black-bordered note. I threw away the protein bars, gave the energy drinks to a shelter, and flushed an opened bottle of Sutent down the drain.

Looking back, memories of my zeal to treat are tinged with sadness. Should I have given up earlier? Would earlier hospice care been kinder? I hadn’t believed Terence was going to die so I had never confronted any of those dilemmas. And I never let us have the chance to say goodbye.

I think had he known the costs, Terence would have objected to spending an amount equivalent to the cost of vaccine for nearly a quarter million children in developing countries. That’s how he would have thought about it.

But when I ask myself whether I would do it all again, the answer is—absolutely. I couldn’t not do it again.

Second-guessing

Late last year, I waded through a snowstorm to Keith Flaherty’s office in Boston, where he had moved to a new job. Did we help Terence or harm him? There’s a possibility, he said, that the treatment actually made the cancer worse, causing it to rage out of control at the end. Or, as another doctor suggested in passing at the time, the strokes were a side effect of the Sutent and not the cancer.

But neither Flaherty nor I believe that. The average patient on Flaherty’s trial got 14 months of extra life. Without any treatment at all, Flaherty estimates that for someone with Terence’s stage of the disease it was three months. Terence got 17 months—still within the realm of chance but on the far-right side of the bell curve.

There is another bell curve that Terence did not live to climb. It charts the survival times for patients treated not just with Sutent, Avastin, and Nexavar, but also Novartis’ (NVS) Afinitor and GlaxoSmithKline’s (GSK) Votrient—both made available since Terence’s death. Doctors and patients now are doing what we dreamed of, staggering one drug after another and buying years more of life.

Slides on the results of Flaherty’s clinical trial, presented at the 2008 meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, showed that Avastin and Nexavar worked well on a wide variety of patients. Only Flaherty and I know that the solitary tick mark at 17 months was Terence.

Only I know that those months included an afternoon looking down at the Mediterranean with Georgia from a sunny balcony in southern Spain. Moving Terry into his college dorm. Celebrating our 20th anniversary with a carriage ride through Philadelphia’s cobbled streets. A final Thanksgiving game of charades with cousins Margo and Glenn.

And one last chance for Terence to pave the way for all those other poor sonsabitches.